Setting the Scene (ACMI, 4 December 2008 – 19 April 2009)

I went along to the Setting the Scene: Film Design from Metropolis to Australia exhibition at ACMI with high hopes and keen interest. The exhibition covers production design in cinema, including the use of sets, locations, and virtual environments. It’s a fantastic and under-explored topic, and one in which I have a lot of interest. As an urban planner, the use of locations and the depiction of our spatial environment interests me a lot (I’ve touched on it in pieces for this site such as this), and the postgraduate research I’m currently doing is focused on these sorts of ideas.

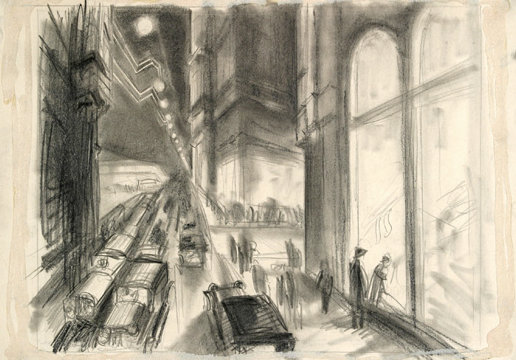

The good aspects of the exhibition flow directly from the inherent strength of the subject matter, and some interesting exhibits. There are things here that film buffs will get a real kick out seeing, such as original design drawings for the modernist house from Tati’s Mon Oncle (as well as a large model of the house); recreated sets from Australia; and – although these have basically nothing to do with the topic of the exhibition – models of vehicles and machines from Speed Racer and the Matrix sequels. The exhibition’s origins as an exhibit by the Deutsche Kinemathek in Berlin is in evidence in the strong focus on European examples: that’s fine, although the fusion between those parts of the exhibition and the material added by ACMI occasionally feels a little awkward. If all you are interested in is seeing some interesting behind-the-scenes material, some good production stills, and a brief gloss over the topic, you might find the exhibition worthwhile.

Unfortunately, these basic merits were overshadowed for me by many disappointing aspects of the exhibition, mostly to do with the way it is presented. ACMI has been around for a few years now, and they should be well and truly across the intricacies of running this kind of heavily media-based exhibition. Unfortunately, the exhibition is pretty much a catalogue of fundamental mistakes: I am quite serious in saying that it would reward close study by those interested in museum curatorship as an example of what not to do.

The first thing that struck me on entering the hall is that it was very dark. No doubt this was partly for mood and partly to facilitate the display of the many videos positioned through the exhibit. Yet the light levels struck me as far too low, and the spot-lighting for individual exhibits was at times poorly thought out. In some cases, for example, wall-mounted pictures were lit by spot-lights from behind the viewing position, so that when you tried to view them you cast a shadow across the exhibit: given the low ambient light level, this made some exhibits very hard to view.

The light level also exacerbated the difficulty of working your way through the exhibition. The exhibition was broken into themes which presented a promising set of subject headings: Spaces of Power, Private Spaces, Labyrinth Spaces, Transit Spaces, Stage Spaces, Virtual Spaces, and Location Spaces. There is, to some extent, a logical order for these exhibits to be viewed, and the exhibits are numbered on the exhibition’s flyer in an order that builds in an approximate chronology to the to the sections on virtual spaces and Baz Luhrmann’s Australia. But to see it in that order you needed to zigzag through the hall; if, like I did (and many others seemed to), you stick to the wall adjacent to the entry and work along it, you see the exhibition in an illogical order. For example, the virtual spaces section is the third you come to, and Australia is about halfway through, but the section on Metropolis is almost the last. The counter-intuitive layout seemed cruelly ironic given the ostensible focus on heightening awareness of space in movies.

Many of the exhibits took the form of video screens, with interviews with production designers, clips from relevant movies, behind-the-scenes footage, or combinations thereof. Video-based presentations are obviously vital to exhibitions of this type, but for an institution totally focused on discussion of the moving image, ACMI seem remarkably clueless about the strengths and weaknesses of such displays, or how they should be presented. There seemed to be a sense that if they just put up informational videos about movies, they were fulfilling their mandate as a centre for the moving image; many displays were the kind of things you’d find as DVD extras (some, like the material on Steven Spielberg’s The Terminal, I suspect were exactly that). Yet on DVD we enjoy these things while sitting on our couch, not standing looking at a wall. Video screens are great for presenting examples from films, and short bits of information, but they have an inherent problem in that the viewer is forced to enjoy them at the speed they unfold. Too much of this exhibition was presented through videos which presented superficial information at too slow a pace, meaning much of the exhibition became a painful exercise of waiting for displays to get to the point. Written boards of information might be less fashionable, but they allow the viewer to quickly scan to the points that interest them. Sometimes newfangled isn’t actually better.

Even the legitimate uses of video presentations seemed poorly thought out. For example, a large video screen in the section on Labyrinth Spaces presented clips from The Name of the Rose, Alien, The Shining, and the most pretentious movie ever made, Last Year at Marienbad. It was an interesting display, but the clips were presented on a big screen one after the other; they cried out to be presented simultaneously on adjacent screens so the viewer could compare one to the other and concentrate on those of most interest. (I appreciate ACMI’s resources aren’t infinite, but keep in mind that there were several dozen video screens in the exhibition as a whole, and ACMI put together a wall of 750 screens for an exhibition a few years ago.)

The relative dearth of written information highlighted what seems to me to be a trend in museum exhibitions, which is to let the items on display do all the talking. This is an unfortunate trend because the items are usually only interesting in context. There was very little information about most of the objects presented: in some cases, for example, I was unsure if models presented were actual production models or simply reconstructions for display purposes. There also wasn’t much information about individual production designers beyond a basic filmography. I would think, for example, that the section on Ken Adam might have warranted some more detailed discussion on the peculiarities of his style or his place in film history, but I was left to fill those gaps myself; this meant I undoubtedly missed the significance of some of the less familiar figures.

I also thought more could have been done to actually explore the issues raised. The introductions to each section were interesting and accessible overviews, but they essentially were stand-alone pieces, without any further follow-up. This meant that the exhibition alluded to all sorts of interest questions, but generally in only the glibbest of ways. For example, the Virtual Spaces exhibit invited some exploration of what it means to take away real places from movies: what are the artistic consequences of such an action? Lars von Treier’s Dogville also copped a mention, and raised similar issues about the absence of place in film. The sections on Metropolis and Spaces of Power raised all sorts of interesting questions about the power of films as an ideological tool (there has been a great deal written, for example, about Metropolis as a precursor to the Nazi state). Yet these issues were alluded to in only the most general way. I appreciate that this was an exhibition, not an essay, but I felt that there was scope for something more than the very generalised discussion of such points.

I freely admit that its possible I’m being too harsh: I am very interested in this subject area, so perhaps I was too critical, or sought a level of discussion that would have bored the punters silly. I’d therefore be interested in hearing what readers thought. Were others as disappointed by this as I was?