Mary and Max (Adam Elliot, 2009)

We might divide artistic achievements into two categories. There are those works in which an artist creates a work that is perfectly tuned to their sensibility and their strengths; and there are those that see an artist break down the barriers to move beyond what we know they are capable of. We should be grateful both types exist. It is the latter kind that surprises us, and that most often push the boundaries of artistic expression. But we need the former kind too. It is films where an artist’s material and approach meld into a perfect union that we tend to see the most perfectly judged works. The animated feature Mary and Max is one of those films: director /screenwriter and designer Adam Elliot knows what his strengths are, and this self-awareness has delivered a pitch-perfect blend of melancholy and humour.

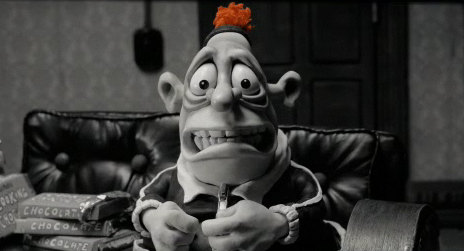

Elliot’s strengths are in ample evidence throughout the film, which tells the story of a long-distance relationship between Mary, a girl from the suburbs of Melbourne, and Max, a socially isolated middle-aged New Yorker. Elliot has been blessed with two quite disparate gifts. Firstly, he is a very strong writer, with a talent for the unstrained blending of the tragic and comic; Mary and Max unfolds largely through voiceover, and you can imagine Elliot making an effective novel from it. Secondly, his grasp of language is supplemented by a wonderful visual style. Elliot designed the film, and the characters and sets are distinctive and serve the story well. Both these talents combine to give vivid portraits of his protagonists’ constrained lives, as well as their respective environments. Elliot uses muted palettes for both settings (brown for the Melbourne suburbs, crisp black and white for New York), and his portrayal of the suburbs in particular shows great fondness and familiarity for his subject. (Elliot might be less familiar with the New York setting, but he is helped in these stretches of the film by a rich and gravely vocal performance by Phillip Seymour Hoffman that is full of local flavour).

That Elliot could get a feature length stop-motion film made in Australia is quite an achievement, given there aren’t many made anywhere. That he could make the film so moving is even more impressive. Elliot is dealing with characters that are bewildered by life and socially isolated, and there are tragic turns along the way. Yet he avoids the film becoming maudlin or sentimental, and at its conclusion it is tear-jerking in the best way. Stop-motion animation is sometimes considered to be the most distancing of animation techniques, as it is hard to get the characters to live on-screen as anything other than painstakingly manipulated toys: hand-drawn and even computer animation can each in their own way give more of a sense of fluidity and life. Even highly successful stop-motion films, like Nick Park’s Wallace and Gromit films, sometimes seem to be constructed to circumvent those weaknesses (in the case of Park’s films, through the firmly comedic tone and set pieces built around intricate Rube Goldberg-style machines, which play on the almost mechanical quality of the animation). Elliot’s achievement in making a stop-motion film that is essentially a dramatic character study shouldn’t be underestimated.

It is therefore not intended as a put-down to return to the thought that I started with, and note that Mary and Max is also carefully built around Elliot’s limitations. Elliot is a skilful writer and a designer, and as in his breakthrough short Harvie Krumpet he plays to those strengths by overlaying narration on top of his striking imagery. The whole story is driven by this approach, with most characters all-but-completely mute, except when we hear their written exchanges through voiceover. Elliot studiously avoids dialogue wherever possible, and he mostly makes it work because the writing is good and the approach thematically suits the story he’s telling here. Yet there are gaps (notably in Mary’s relationship with her husband) where the near-complete absence of verbal interaction between characters seems contrived and a little distracting. Actually staging a scene and telling us his characters’ feelings through actions and words, rather than a Barry Humphries voiceover, is a challenge Elliot seemingly doesn’t want to tackle.

Elliot seems, then, to be an animation director who actually animates only reluctantly, and in Mary and Max his other immense talents make it work. It will be interesting to see whether he can make a different kind of animated film, one in which he goes beyond the safety net of voiceovers and striking design. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if he instead makes a Tim Burton-style transition to live-action, where he might be able to still use his strengths but shake off his limitations as an animator.