Moon (Duncan Jones, 2009)

As I suggested back in 2007, when reviewing Danny Boyle’s Sunshine, anyone trying to make an old-school intellectually-driven “hard” science fiction film faces a battle against both familiarity and economics. Familiarity, in that the key works in the genre (2001, Solaris, Silent Running, Dark Star, and so on) have mined so much of the territory available against the genre that it can be hard for newcomers to find new creative territory. And economics, in that those who finance such movies struggle with the constraint that in order to afford the special effects their plots require, they may get pushed to include action and spectacle that is at odds with the more cerebral thrust of their story. Boyle struggled gallantly with both constraints without quite prevailing over them, but now we have Duncan Jones’ Moon to demonstrate decisively that it is still possible to make smart, original science fiction that isn’t intimidated by history.

The film is set in the near future when the Earth is dependent on resources mined from the moon to meet its energy needs. Astronaut Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell) is the sole staff member in a lunar mining station, approaching three years of service with only the mandatory creepy-voiced computer to keep him company. (The computer is called Gerty, perhaps in a nod to Winsor McCay, and is voiced by Kevin Spacey to make sure the audience doesn’t trust it). Bell is a few weeks away from being able to go home, but his sanity is being tested as he approaches the finishing line: he is seeing people around the base. Then one day, he encounters himself.

What follows from that point is a slow burn, but always a fascinating one. Moon is a puzzle movie, where we follow the hero as he tries to work out what is going on. It plays that puzzle out without cheating, never using Bell’s hallucinations as an excuse for the film to simply not make sense. And while some of its predecessors were the filmic equivalents of chess nerds – brainy but dull – Moon is engrossing throughout. The conceit of Bell meeting and interacting with himself is successfully milked for comic and dramatic potential; as often occurs in such stories, Bell doesn’t get along with himself. Here, though, there’s a thematic point to be made from that conflict. One of the versions of Bell is as he was when he arrived on the base, and one is Bell after three years, and the interaction between the cocky and fit newcomer and the frazzled and deteriorating veteran dramatically illustrates the toll that the period on the base has taken on the astronaut.

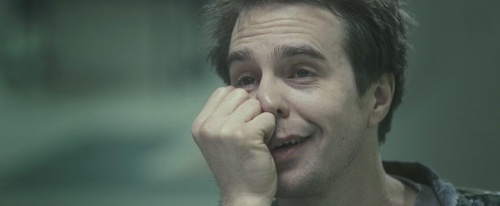

Since the film isolates two version of one character on the base, and asks them to carry the film, the film places great weight on Sam Rockwell. He meets the challenge with an extraordinary performance, yet another impressive entry in his resume. Rockwell makes a withdrawn and surly character likable, while managing the Bell double act with confidence. Bell argues with himself, fights himself, and plays table tennis with himself, and at all times the interaction is fluid and natural. The special effects to achieve the multiple Bells are seamless and – crucially – not too showy, so the trickery never becomes distracting. For all the slick effects, however, Rockwell is crucial to making that work.

The film’s only other effects are relatively simple exteriors, achieved largely with models. (Reportedly, many of the model crew were veterans from Alien, and the film has a similar no-thrills aesthetic in its effects). The beauty of the film, however, is that it can keep the action largely on the base, and almost entirely on that one great central performance. This frees up the film to use its small budget very effectively: while very polished, the film remains a close cousin to ultra-low-budget predecessors like John Carpenter’s Dark Star. And by keeping it (relatively) cheap, Jones seems to have bought himself freedom to make the film as he sees fit. This means no assault by CG moon-monsters, no mandatory horror overtones, no climactic fight over a deep lunar abyss. Jones instead makes the film absorbing with smaller touches that show an intelligent filmmaker at work: plot points that subvert our genre-honed expectations; an effectively literal ticking clock (reminiscent of Outland) to build tension; and having the confidence in the audience to not telegraph every plot point or to feel every point needs to be carefully explained.

Moon is Jones’ debut feature, which given the confidence of his filmmaking here is cause for amazement. The terrific news, however, is that Jones apparently sees this as the first in a trilogy. That’s cause for celebration.

Related Items

For my review of Sunshine, click here.