Alice in Wonderland (Tim Burton, 2010)

The best-remembered of the many adaptations of Lewis Carroll’s two “Alice” books is the animated adaptation released by the Disney Studio in 1951. Walt Disney, who worked on his version on and off for the best part of fifteen years, was renowned for his story sense: an uncanny ability to sense and solve story problems, as well as a knack judging the taste of the public. So what did he make of Alice in Wonderland as a story? Well how about:

“[I got] trapped into making Alice in Wonderland against my better judgement.”

And:

“[It was] a terrible disappointment.”

And:

“We just didn’t feel a thing, but we were forcing ourselves to do it.”

And:

“The picture was filled with weird characters.”

Disney had realised (too late) that Carroll’s books are essentially the opposite of what a Hollywood narrative is supposed to be. They centre on a character who we never identify with on any emotional level; who embarks on her adventures without any clear purpose; and who is tormented by a series of unsympathetic characters for no clear reason. Carroll therefore breaks all the rules of conventional Hollywood narrative: that we have an emotional connection with the protagonist; that the plot unfolds through a series of events that happen for clearly outlined reasons; and that characters have clear motivations for their actions. The randomness, nonsense, and mind games of Carroll’s Wonderland are a big ask for Hollywood.

Tim Burton’s adaptation tries to solve that problem by grafting a Narnia-esque plot onto Carroll’s. Alice – played by Mia Wasikowksa – returns to a Wonderland after having forgotten her previous visits, where the various familiar residents (the White Rabbitt, Mad Hatter, Cheshire Cat, Tweedledum, and Tweedledee) see her as an almost messianic figure. Wonderland, like Narnia in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, has fallen under the tyrannic influence of the Queen of Hearts, and Alice is prophesised as the one to deliver them from tyranny.

If this sounds very generic, you’re right: it is. That’s not in itself fatal – plenty of adaptations of classics that are light on narrative have made things work by bolting on a formulaic plot. But the very fabric of Carroll’s work resists such an attempt. Here, for example, various terms from Carroll’s classic nonsense poem “Jabberwocky” (the only piece of Carroll writing to be quoted at any length in the film) are invested with plot significance: Alice must slay the Jabberwocky using the Vorpal Sword on Frabjous Day. Yet the whole point of Carroll’s poem was that it was nonsense, and that his made up words like “vorpal” and “frabjous” were there for their feel: Carroll was playing games with what is left once meaning is removed from language. Turning the “Vorpal Sword” into Excalibur misses the point; much more seriously, though, it takes the fun out. If any story shouldn’t be about plot mechanics and character growth and mystical quests, it’s Alice in Wonderland.

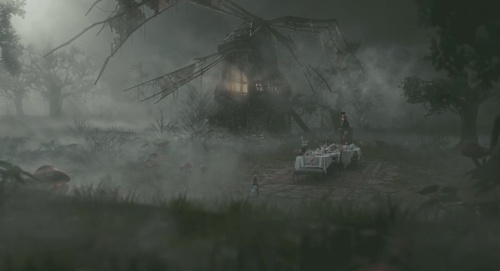

Tim Burton’s visual sense might have been expected to be a more natural fit for Carroll. Yet there’s something underwhelming about the computer-generated environments of Wonderland. I think there’s a sense in which technology has allowed conceptual visions to be realised with too much fidelity. If you’ve ever looked through those glossy “art of” books of conceptual art for a fantasy film, you’ll know how the art usually looks at once more amazing but also somehow more unmistakeably imaginary than what ends up on screen. The process of filming a production used to make those visions more tangible: sets would be built, locations scouted, and designs refined into something that could be placed before a camera. In the process, the vision became less wondrous, but also more concrete. Here, though, computer effects have seemingly allowed those original visions to be transferred straight to the screen, and Alice seems to be wandering through still-intangible conceptual art. As much as this might have theoretically have been the perfect production for such an airless, ethereal world, it’s just another distancing element. Burton can’t have it both ways: if we’re to care for the plight of the Wonderlandians in his grand final battle, he has to give his world some substance. But who will ever believe in the plight of this Wonderland? His CG frippery – further ruined in 3D by the distracting, blurry, discoloured process – never seems more than a pretty picture.

Considered as a procession of character cameos (which, of course, is essentially what the novels were) the film is a little more successful. Johnny Depp’s Mad Hatter is certainly an eye catching creation, if ultimately both over- and mis-used. Helena Bonham Carter is enjoyable to watch as the Queen of Hearts, who (in the film’s best special effect) has a regular sized head on a tiny body. Bonham Carter is pretty much channelling Miranda Richardson’s classic portrayal of Queen Elizabeth from Blackadder 2, but that’s fine with me: it’s just a shame that the script (by Linda Woolverton) doesn’t have a bit more fun with the potential of the role. Matt Lucas makes for an eye-popping but somewhat wasted Tweedledum and Tweedledee, while various other good actors (Stephen Fry, Michael Sheen, Alan Rickman) turn up in voice roles. None of these characters, however, get much of Carroll’s original dialogue, or any suitably witty replacement.

Which somewhat makes you wonder what Burton appreciated about the original. Was it just a casting exercise? The idea of Depp as the Hatter, Fry as the Cheshire Cat, and Williams as the Tweedles does indeed seem irresistible. But if you strip the riddles, mind games, and non-sequiters out of Carroll, what is the point in doing it?