Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock), 1960

I’m told that a small boy who stayed up to be scared by this masterpiece said afterwards “I liked it, but it made me want to sleep in Mummy’s bed.” – Kenneth Tynan(1)

If you were to pick the most famous single scene from movie history, you’d probably have to choose the shower scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. Film buffs might shout “Odessa Steps” at you, but while Eisenstein’s bravura sequence is more important (if only for being earlier, and arguably a model for Hitchcock), I doubt any other moment in 100 years of cinema has been the subject of as many imitations, homages, and parodies. The whole film, in fact, has been so endlessly reworked, remade, and revisited, that today’s viewers will usually come to Psycho with much of the film already in their head.

There are two great pities about this, though. The first is that so few people do even get to the point of worshipping at the Psycho altar. Sure, films such as Scream pay homage, and we keep hearing about the modern audience’s sophistication when it comes to recognising and processing film references. Yet I think the allusionism has gotten so widespread that part of the art is recognising the reference without seeing the original: you can get a reference to Psycho in Scream, say, by connecting it with that recreation in a Simpsons episode or a Mel Brooks take-off.

The other shame is that it is hard – impossible, really – to come to the film clean. The film is still very unsettling, but I can only imagine what it would have been like to see the film in 1960. Nobody today can see the film without knowing, for example, that Janet Leigh’s Marion Crane will be killed early on, and few would have any confusion about who exactly “Mother” is. And the film – with its emphasis on sex and explicit violence – was far ahead of its time. Despite the film obviously having laid down the template for the modern horror film, it took a long time for the trickle of imitations to build into the flood of video horror in the 1980s. (It was eight years before George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, another six to Tobe Hooper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre(2), and four more beyond that to John Carpenter’s Halloween.)

Shock value might diminish with time, but artistry doesn’t, which is why Psycho still works. Hitchcock’s direction is characteristically tightly controlled, and astonishingly inventive for a director who had already been directing for thirty-five years. Whereas most of the breakthrough modern horror films (such as those mentioned above) were the works of young directors at the start of their careers, Psycho was the work of an Oscar nominated studio veteran whose earliest films predated sound. Working on a low budget – necessitated by the risky subject – Hitchcock’s work is as stylistically adventurous and technically polished as anything he did. (Interestingly, it is his bigger budget features that usually seem more dated from a technical standpoint.) His crew supported him with excellent work all round, from Bernard Herrman’s classic score to Saul Bass’s memorable titles.

And of course Hitchcock was working from a superior script by Joseph Stefano. Stefano, perhaps sensing the film’s secrets would be either guessed or leaked, wrote the film in such a way that it works even once you know who “Mother” is. The script has a dark, dark wit that must have greatly tickled Hitchcock. The most obvious examples are the early conversations between Norman and Marion – these are unsettling, and work as exposition, but they are also filled with macabre humour. Norman, for example, is lugging the corpse of his mother about the house, yet is religiously changing the unused linen because he finds the smell of it too “creepy.” Another example is the exchange between the highway cop and Marion, after she’s spent her first night on the road sleeping in her car. Next time she should book into a motel, he says… “just to be safe.”

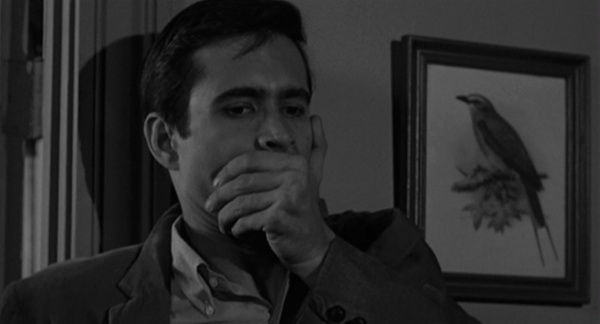

If there is one single contribution to the film that matches Hitchcock’s, though, it would be Anthony Perkins’ performance as Norman. Horror movies are full of pathetic figures that are both creepy and endearing, but I’m not sure anyone has ever simultaneously conveyed both aspects as fully Perkins does here. The madness is in many ways a peripheral detail: it’s a classic portrait of a decent, charming guy saddled by deep feelings of inadequacy and shyness. Perhaps the greatest tribute to the film is that the relationship between Norman and his Mother would still be interesting even if she weren’t just in his head, as Norman’s unreciprocated devotion is legitimately touching. He’s given everything up for her (including his sanity, unfortunately), but she doesn’t value him at all. Danny Peary has pointed out the sad detail that while Norman spends most of the film covering up for Mother, she immediately rats on him at film’s end. And while Norman feels that “a boy’s best friend is his Mother,” he knows she doesn’t value the relationship so highly, as “a son is a poor substitute for a lover.”

1. I’ve taken this quote from Danny Peary’s Cult Movies 3, which includes an excellent discussion of the film.

2. Hooper’s film was largely inspired by the story of Ed Gein, the same real-life serial killer who inspired Robert Bloch’s original source novel for Psycho.