American Graffiti (George Lucas, 1973) and

Two-Lane Blacktop (Monte Hellman, 1971)

The pair of car-culture themed films being screened by the Astor theatre in Melbourne as a double bill from the 24th to 30th of April make a fascinating pair; at once complementary and highly contrasting.

The pair of car-culture themed films being screened by the Astor theatre in Melbourne as a double bill from the 24th to 30th of April make a fascinating pair; at once complementary and highly contrasting.

George Lucas’ American Graffiti was an exercise in instant nostalgia: released in 1973, it had the temerity to be nostalgic for 1962, only eleven years before. At one level this might be partly excused by the extent of social and political change that occurred in those years. These days, however, we might more readily cast it as a sign of something lacking in George Lucas. He’s known now as a cold and technocratic filmmaker, more interested in fantasy and machinery than with people; and it’s easy to see American Graffiti as part of that pattern. Its escapist revelrie of an adolescence untouched by the social upheavals of the 1960s but glammed up by rock and roll, drive-in diners and hot rods can be painted as Lucas’ rejection of all subject matter that was more complex, troubling, contemporary, and adult.

And yet… that’s letting its spot in Lucas’ filmography (and film history for that matter) completely overwhelm the qualities of the film itself. Perhaps the film was an early sign of the traits that would destroy Lucas as a filmmaker; perhaps there is something cold and inhuman at its core. Neither truth would detract from the delicate balance that Lucas achieved here. At a simple aesthetic level it is dazzling, marrying the visuals of the gleaming metal and headlights of the cruising cars with an extraordinary sound track of late 50s and early 60s rock. The cinematography mixes a strong sense for the aesthetics of the cars as an almost abstract visual spectacle, with a rougher semi-documentary feel (often featuring handheld cameras and long lenses) documenting the characters within. The film feels as if it was illuminated by available light – it constantly skirts at the edge of being underlit – and yet nevertheless manages to evoke a golden, elegaic tone to convey its sense of a wondrous bygone era. Aurally, the film’s rock music is blended into an almost omnipresent sound montage that establishes the shared musical experiences that links the characters. At crucial moments it is complemented by creative use of sound effects to substitute for a score, as when Curt (Richard Dreyfuss) tries to sabotage a police car, the build-up to which is the menacing cacophony of a passing train.

That technical sureness isn’t a surprise, given the trajectory of Lucas’ later career. Yet the real success of his film is the humanity and humour with which he deals with his characters. No doubt Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz warmed up and polished his screenplay (they did the same, uncredited, for Star Wars) but the story is compassionately delivered by the director. Lucas was notoriously uncommunicative with his actors, but he nevertheless got terrific performances from his cast here: Ron Howard effectively conveys the immaturity and self-indulgence underlying the cocky Steve; Cindy Williams gives dignity and an emotional reality to the role of his more perceptive and intelligent girlfriend Laurie; Richard Dreyfuss is all charisma as the idealistic but hesitant Curt; Charles Martin Smith is endearing as the bumbling nerd Terry; and Mackenzie Phillips is hugely appealing as Carol, the twelve-year-old who ends up hitching a ride with Paul Le Mat’s rebellious but good-hearted drag racer. (The main point of nostalgia seeing the film now, in fact, is seeing actors such as Dreyfuss, Smith and Harrison Ford play teenagers). The stories are constantly funny and at key moments – such as the dance between Steve and Laurie – quite touching. Technocrat he may be, but Lucas’ attention to the human component of his story here, at least, is hard to fault.

If we want to fault him for escapism and starry-eyed nostalgia we need to recognise, too, that the film’s worst moment is the attempt contextualise the film’s look backward. At the conclusion we get a title card that – with, it must be said, inexcusable sexism – tells us what happened to the four male characters in the years after 1962 (Lucas would go on to produce More American Graffiti, which expanded on this after-story). The mixed fortunes of the characters are the film’s nod to the social and political realities of the decade that followed, and it seems out of place and needless. The film would have been stronger had it been purely nostalgic and feel-good, referencing what lay after the film’s golden age more obliquely.

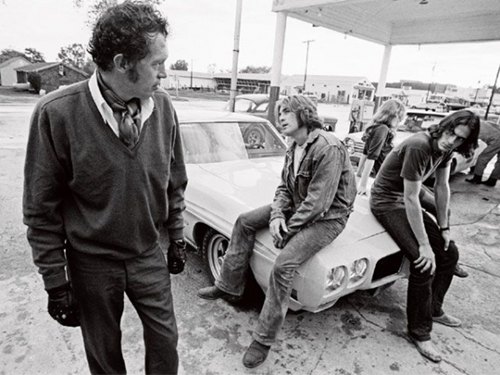

Paired with American Graffiti on this double bill is Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop, which was released two years before Lucas’ film, in 1971. The transition between the two films is particularly neat, given that Lucas’ ends with a drag race and Hellman’s starts with one. Both focus on car culture, and similarly fetishise the machinery of automobiles; both in their own way address the turbulence of the latter 1960s and early 1970s. Where Lucas did so by ignoring the present and evoking a past before those troubles, where cruising was part of a glorious teenage sunset, Hellman makes disillusionment with the present-day 1970s his subject. He focuses on two unnamed youths (known only as the Driver and the Mechanic, and played by musicians James Taylor and Brian Wilson) who have seemingly turned their back on society in order to cruise the highways and participate in races; along the way they interact with the hot-headed GTO (Warren Oates) and an unnamed girl who hitches a rides with them (Laurie Bird).

Hellman’s film is more reputable than Lucas’: by focussing on these detached characters it avoids the easy gratification of nostalgia and confronts the alienation of its protagonists head-on. It is also a more enigmatic film, making its audience work harder. The Driver and The Mechanic are sullen and uncommunicative, and hence make unsympathetic and obtuse protagonists (their dull manner and near-lookalike staus reminded me of Poole and Bowman from 2001: A Space Odyssey). Oates’ GTO is much more outspoken and entertaining to watch, but it quickly becomes apparent he is an almost compulsive liar, so we can only guess at his true background. What unites all three characters is a love of cars and a disengagement from the rest of society: the Driver and Mechanic seem to have dropped out, while we can infer that the older GTO has probably burnt out in a mid-life crisis.

The difficulty for Hellman is that alienation is a tricky subject to draw much from. Once we establish that they are disengaged from all around them, it’s hard for the audience to learn much more about them; for that matter it’s hard for Hellman to make much more of a point. The film does gather steam as the Driver and Mechanic make a wager with GTO as to who can reach Washington D.C. first. This concession to conventional narrative adds interest; and the characters’ erratic pursuit of their goal (the Mechanic and Driver, in particular, seem uninterested in winning) adds humour and a precious chance to define the characters through their actions. Yet ultimately that plot strand, too, only sustains the film so far. The film is beautifully shot, with Hellman’s feel for the cars, the landscape, the towns and the period becoming (along with Oates’ performance) the film’s chief attraction. But ultimately it founders somewhat on the futility of its own journey: while the film’s nihilistic conclusion makes it clear this was intentional, it’s hard not to walk out feeling deflated.

Perhaps this sounds like I wanted Hellman to make a more mainstream and accessible film, as Lucas did. That’s not quite right. I’ve seen this film made as a commercial film: it was called Smokey and the Bandit and I wouldn’t wish that on anyone. My observation – and any long-time readers will know I’ve made this point before, notably here – is more that the conventions of both art cinema and mainstream narrative cinema are actually more interesting when they cross-pollinate. American Graffiti benefits from its willingness to take on a multi-stranded narrative and a bolder visual and aural aesthetic than a more conventional teen picture; Two-Lane Blacktop’s best moments are those where it is willing to show a genre film’s interest in character and – dare I say it – plot. Both are fascinating films, and those in Melbourne would be well served to seek out the Astor’s short season.