The big planning story of the last few weeks has been the release of the draft new metropolitan strategy, Plan Melbourne. I don’t yet have any detailed comments to make on the plan itself, as I haven’t had a chance to look through it in detail. However I did want to highlight one aspect of the plan relating to notice rights around housing, as it closely relates to a few things I’ve written about before here (namely the new zones and VicSmart). This is something that I know has been widely discussed in the industry, but I haven’t seen an informed version of the discussion in the wider press. I also thought it would be worth covering just to spell out some of the chapter and verse of what has previously been said on this topic, since a fair few of the relevant documents are either hard to find or simply no longer available through the Department’s website.

On the day that the strategy was released, there was a fair bit of publicity about proposed exemptions from notice and review for medium and higher density housing. This is an important issue because it relates to the roll-out of the new zones that is happening as we speak: the government launched new residential zones in July, and Councils have a year to choose where to apply them. Any change in how they are to work is therefore an urgent issue, which potentially needs to be resolved much sooner than the metropolitan strategy.

It is worth, at this point, reminding ourselves where the zone discussion started. The proposed “three speed” zones have been a key to the Department’s planning reform since 2007, with the release of Making Local Policy Stronger. That review really kicked the idea off with its talk of “go go,” “slow go,” and “no go” residential zones:

While some councils proactively identify “go go” (substantial change), “slow go” (incremental change) or “no go” (minimal change) areas in their local planning policy framework, they do not have a suite of zones that provides a ‘neat fit’.

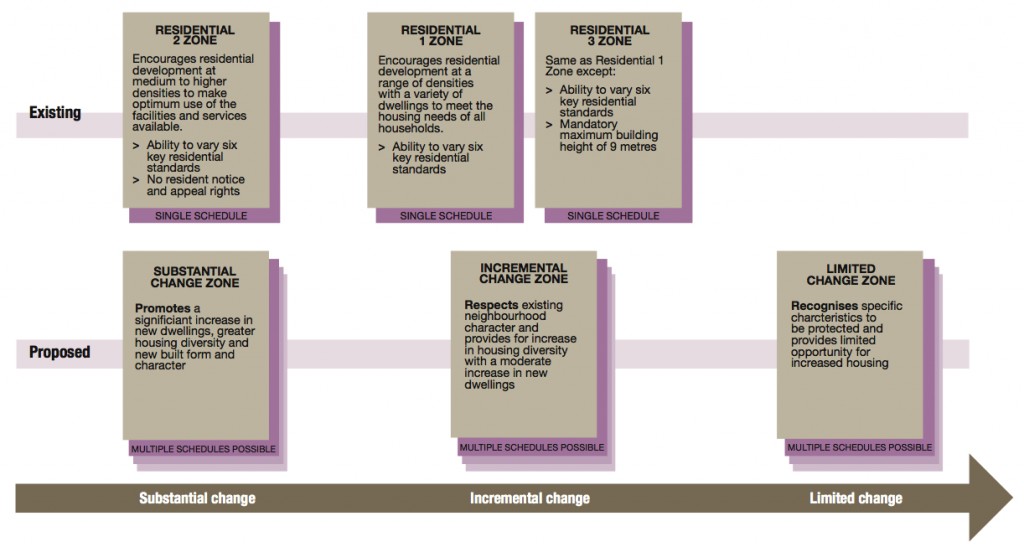

The former Labor government then went on to a zone review, with a discussion paper released in February 2008, outlining the three new proposed zones. Lining up with the Making Local Policy Stronger recommendations, those zones were to be called the Substantial Change, Incremental Change and Limited Change zones.

In fact, there already were three zones intended to fulfill those roles: the Residential 2 Zone for growth, the Residential 1 Zone for the standard moderate growth scenario, and the Residential 3 zone for limiting change. (The last option could also be achieved by combining zones with other overlay controls, such as the Neighbourhood Character Overlay). This was acknowledged in the 2008 zone review, although it was implied in the diagram below (click to enlarge) that the Residential 3 Zone was not serving its intended function as the limited change zone, by remapping it to count as an incremental change zone. That was always a fiddle, though: I look at the diagram below and the key problem seems to be some sort of issue with the right hand margin.

So if three speed zones have existed all along, what was the actual problem with the old zones?

So if three speed zones have existed all along, what was the actual problem with the old zones?

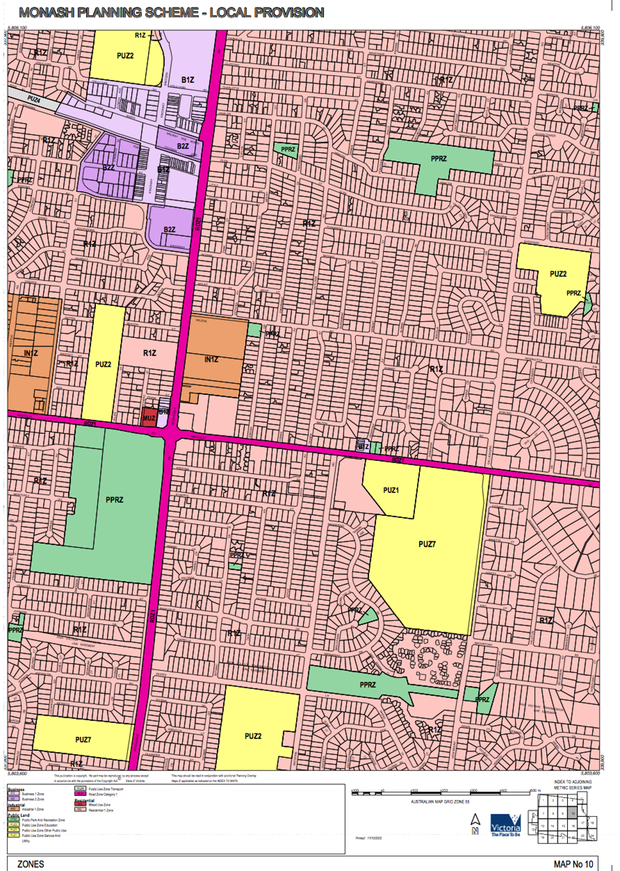

The first obvious one was application; the full suite simply wasn’t very widely applied. The map below is one of Monash’s zoning maps, from Glen Waverley, and shows the classic suburban sea of pink, indicating the near universal application of the Residential 1 Zone. Even around the train station in the top left, once you get beyond the business-zoned areas, there’s no use of the existing higher growth zone (Residential 2).

Part of the answer, then, might be about simply forcing Councils to use all three zones more. However, the other point prompted by a map like that above is whether there is something about the design of the pre-existing three speeds of zone that made Councils reluctant to use them. In particular, why were Councils reluctant to apply the higher-growth Residential 2 zone?

That answer was never very mysterious. It is acknowledged in Making Local Policy Stronger: Councils didn’t use Residential 2 because it didn’t allow for third party notice and review for medium and higher density housing. So in those areas, neighbours wouldn’t get informed of such applications at all, and wouldn’t have any rights to go to VCAT. Even when Councils were committed to growth, not many wanted to be that aggressive, so the zone was under-applied. So, counter-intuitively, the tool for high growth was under-performing because it was too powerful.

The feeling was that a different tool was needed. This would be a higher growth zone that sent a strong signal to the market that growth was appropriate and could vary some restrictive ResCode standards, but which wasn’t so aggressive in cutting the community out of the process. This was how the advisory committee looking at Labor’s proposed revised zones saw it:

The Advisory Committee considers that the reintroduction of advertising and appeal provisions for use and development in the Substantial Change Zone should be supported. It is commonly held that the implementation of the Residential 2 Zone has been hampered by the removal of third party notice and appeal rights. This makes the zone unattractive to councils and is currently applied in a limited number of planning schemes.

The Advisory Committee supports the much wider application of the Substantial Change Zone, and as such notice and appeal provisions are generally appropriate.

The reintroduction of notice and review rights in the Substantial Change zone was therefore one of the key design changes made in the new zones. It survived the re-branding of the new zones that occurred under the new government: when the revised zones were dusted off and relaunched, the Substantial Change Zone became the Residential Growth Zone, but it retained the reintroduction of notice and review.

Whether this and a few other design tweaks (such as increased customisability) warranted the six years it took to get from Making Local Policy to the release of the final new zones in July this year is doubtful. However, having been through that journey, we are now in the crucial phase of actually working out what goes where. While I suspect that there was a shorter route to the current zones, the time may yet be worth it if the current implementation phase results in comprehensive review of the placement of residential zones, and increased utilisation of the Residential Growth Zone.

This is where the draft metropolitan strategy comes in. Page 67 of the new strategy includes as an initiative “extend the VicSmart system to multi-unit development,” and elaborates as follows:

A code assessment approach to multi-unit development will provide clarity as to the type of development that is acceptable in defined locations. This will provide residents and developers with increased certainty as to the type of development that can occur in specific precincts. A code assessment approach using the VicSmart system is also likely to improve housing affordability by reducing the length of the approvals process and reducing associated financing costs for the development sector.

As implementation, it then proposes to:

Prepare and implement planning provisions for a code assessment approach for multi-dwelling development. This should apply only in appropriately defined areas, such as the Residential Growth Zone…

While VicSmart has yet to be finalised, it is, by definition, a process that is exempt from notice and review. That is also true of code assessment, which is actually – as even the Department have admitted – a different thing to what VicSmart ended up being. So whichever of code assessment or VicSmart ends up applying in the Residential Growth Zone, either way notice or review rights would disappear within that zone, if Plan Melbourne is to be believed.

So we have gone around in a grand circle. After a six year zone review, Plan Melbourne suggests we will go back to a higher-growth zone with no notice rights. Worse, this suggestion has been dropped out there without further explanation just as Councils are in the midst of working out where those zones should apply.

It is possible this is just some mistake, coming about from the left hand not knowing what the right hand is doing. Certainly the passages above sound like they were an offhand comment written by someone who doesn’t really know what VicSmart is. Firstly, VicSmart isn’t code assessment (and again, that’s not just me saying that: the Department’s own material draws this distinction). Secondly, VicSmart goes far beyond notice exemptions in ways that would make it a very poor fit for complex applications such as multi-dwelling housing, notably by banning further information requests and imposing very tight ten-day time-frames. Certainly using VicSmart in this way is directly contrary to what the 2012 Vic Smart material said. Those releases specifically stated as follows:

Can units be built next to me without notice under VicSmart?

No. Complex permit applications will not be assessed under the VicSmart process. They will be assessed by the usual planning permit process.

Will permits for high rise projects be issued under VicSmart?

No. Applications for high rise projects will not be assessed under the VicSmart process. They will be assessed by the usual planning permit process.

The problem is, even if we assume the references in Plan Melbourne to VicSmart are in error, the suggestion that notice exemptions would apply in the Residential Growth Zone seems unambiguous and is hard to read as a mistake. And even if the Department do walk back from it, the damage will be done if they are not very quick about it. It’s not good enough for them to wait and see how the consultation on Plan Melbourne goes: that’s open until 6 December and any changes presumably won’t happen until well into next year. Meanwhile, the consultation for the application of new zones is underway right now, and the prospect of notice exemptions in the Residential Growth Zone is likely to discourage Councils from using it.

In that scenario, six years of work on zone reviews will have been squandered, and we’ll be back where we were in 2007. If the Department don’t issue some sort of clarification quickly, that sea of pink zoning out in the suburbs is likely to persist.