The Sea Inside (Alejandro Amenábar, 2004)

The Sea Inside (Alejandro Amenábar, 2004)

Spanish Title: Mar Adentro

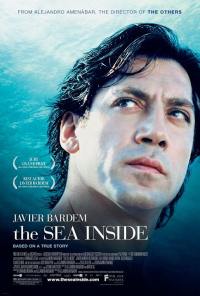

The posters and press ads for Alejandro Amenábar’s The Sea Inside are not terribly enlightening: the face of hunky Javier Bardem dominates the image, set against the featureless blue of the sea. There is no indication of the content of the film, which centres on the quest by Ramón Sampedro (Bardem), a quadraplegic, to end his own life. Yet there is a greater honesty at work here, for the film is not the worthy-but-gruelling experience that the material might have you expecting. The Sea Inside is a tender and often funny film that is always engrossing and ultimately deeply moving.

The film is based upon a true Spanish case, and its arrival in Australia so soon after the euthanasia debate that surrounded both Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar Baby and the very sad real-life case of Terri Schiavo will, no doubt, tie the film into that debate. Nevertheless, I hope the film isn’t seen purely as a polemic. In the film Ramón is insistent that he is speaking only about his own situation and not about others with debilitating conditions, and I think this is a healthy approach to the film. Cinema is extremely effective at mounting an emotional argument, and much less capable of carrying an intellectual one. I’m not completely convinced, on an intellectual level, about the merit of allowing euthanasia for quadraplegics: I’m sure most quadraplegics who go on to live rewarding lives have also faced deep despair during which death must have seemed attractive. But the film concentrates on this man, and whatever one might think of his decision, the story of his struggle is beautifully told.

Which is not to say that the film avoids the moral and personal complications that arise around the issue of euthanasia. Not least of these is the figure of Ramón himself: while resolute and unflinching in his wish to die, his warmth and personal charisma means that value of his life cannot be dismissed easily. The film also explores the human impact upon those around Ramón, facing up to the deep ramifications his decision has for others. There are those who come to share Ramón’s desire for escape through death; those who feel burdened providing his care but nevertheless oppose his decision; and those for whom he provides the strength to go on living.

At the centre of the film is Javier Bardem as Ramón. It is a staggering performance. Bardem has undergone an enormous physical transformation – aided by flawless and unobtrusive make-up work – but it is not a showy performance in the My Left Foot tradition. Bardem’s achievement is not in portraying the physical ailments that imprison Ramón: it is in making Ramón such an engaging and complete personality. Despite Ramón’s wish to die, he is not a depressive person, and provides much of the film’s humour. The supporting cast is also very good, with Ramón’s family and associates all very real and all sharply distinct in their take on his dilemma. The film follows the space of about two years in the life of both Ramón and his circle of supporters, and the phases of life that they pass through are a counterpoint to the frozen nature of Ramón’s existence.

As good as Bardem and the rest of the cast are, however, the main achievement is that of Alejandro Amenábar, who directed the film and co-wrote the screenplay with Mateo Gil. This could easily have been a telemovie-style disease-of-the-week weepie, but Amenábar lifts the film above that level. The obvious approach would have been to revel in the difficulties of Ramón’s existence to show exactly why he felt his life lacked dignity. Such an approach would have been honest and would have helped us understand Ramón’s decision, but it also would have turned the film into a gruelling slog that ultimately victimised and dehumanised him. The important details in this film are not the physical symptoms and humiliations of his life as a quadraplegic – the discomfort, needing to be bathed and changed, the difficulties in performing simple tasks, and so on – but rather the gulf between Ramón and other people that his immobility creates. Talking to his lawyer, he talks of the enormous abyss that the last three feet between them represents: it is, as he puts it, an impossible journey, and that’s the torture of his condition.

Amenábar maintains the tone of the film perfectly: it doesn’t shirk the grimness of Ramón’s situation, but is not an ordeal for the audience either. The film is emotionally warm, full of humour, and is beautiful to look at. Rather than forcing the audience into Ramón’s physical plight and grounding the film in his room, Amenábar explores his internal life and his fantasies of escape. These sequences could easily have seemed out of place, but instead they round out his character and let us truly appreciate his loss: the sequence in which he dreams of flight outside his window is truly exhilarating. The film is wonderfully shot throughout, with an expansiveness that defies its subject matter, and its beauty is enhanced further by Amenábar’s sensitive but emotional musical score. Despite its subject matter, this is not a film that encourages a dim view of life. As Ramón rides in a taxi away from his home for the last time, the camera drinks in the richness of the landscape he looks out on: Amenábar isn’t afraid to complicate his film by showing that there is still a lot to live for.

Because Amenábar develops the personalities and lives of Ramón and the people around him so sympathetically, we don’t underestimate either the good or the bad in his life. Ramón’s desire to die is therefore shown not simply as a reaction to a ghastly set of circumstances, but a decision made by a fully rounded personality whom we have come to know and respect. Most of all, Amenábar is able to navigate the tricky distinction between a life that has become an ordeal to live, and a life that is worthless. By showing Ramón as such a rich and multi-faceted person, Amenábar has achieved an apparent contradiction: he has made a film about assisted suicide that is ultimately life-affirming. It is a truly triumphant film.

Originally published at InFilm Australia.