Munich (Steven Spielberg, 2005)

Some day soon, perhaps, Steven Spielberg may be able to make adult and dark movies without prompting raised eyebrows. The undertone of much recent writing about Spielberg seems to be that his recent films amount to some sort of con: deep down he is still that saccharine confectioner that he was pigeon-holed as in the early 1980s, and all these challenging and important films he has made are just a kind of veneer that hide the real director underneath. This attitude doesn’t seem to be dislodged by the fact that his exercises in pure cornball schmaltz (I’d nominate The Color Purple, Always, Hook, and The Terminal) are now massively outnumbered by films that bear little or no relationship to the cliché of Spielberg as a relentlessly cheery sentimentalist. At some point, however, his resume is going to have to stop being treated as a series of aberrant examples, and critics are going to have to roll up their sleeves and start the belated task of reappraising his work.

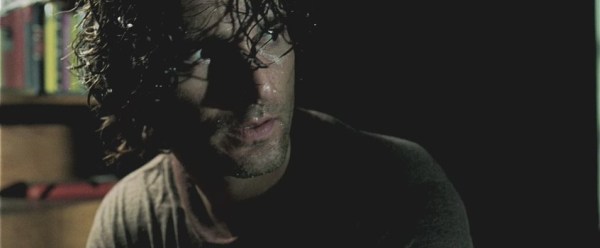

His latest, Munich, is a fictionalised account of the events that followed the kidnapping (and, ultimately, murder) of Israeli athletes by the terrorist group Black September at the Munich Olympics in 1972. While the film does cover the events at the Olympics themselves, its principal focus is on Israel’s response. The film follows a group of Israeli agents sent to assassinate those that the Israeli government believed organised the Munich operation. It is constructed as a thriller, with the narrative built around the assassination attempts by the Israelis, but the core of the film is its exploration of the questions raised by the killings. The Israeli team starts out full of enthusiasm and with few doubts, but as the number of dead increases, they start to re-examine their role. The film charts the way in which the cycle of reprisals escalates, with the assassinations seeming to achieve only dubious benefits. Eric Bana is excellent as Avner, the leader of the squad: Bana conveys his eagerness to do his job, but also shows the way in which he is eaten away inside by guilt and paranoia as the mission wears on.

Munich is, of course, set in the seventies, and it almost feels like it was made at that time. The production design is faultlessly convincing, and even the cinematography (by Janusz Kaminski) has the desaturated look of seventies film stock. Its whole approach recalls dramas from the era: in its chronicling of the preparation for assassination, for example, it strongly recalls Fred Zinnemann’s Day of the Jackal, from 1973. It’s a reminder of what Spielberg was in this decade: with Duel, Jaws and even portions of Close Encounters, Spielberg built a reputation in the 1970s as a budding neo-Hitchcock. Spielberg has been able to show off his skills as a suspense filmmaker in individual sequences since, but in Munich we get a rare and welcome chance to see him flex these muscles over the length of a whole film. His assembly of the assassination setpieces is exemplary, and Munich demands to be seen simply for the chance to watch one of cinema’s finest master craftsmen at work. A sequence involving a bombed phone, for example, unfolds with a meticulous precision that creates almost unbearable tension. Things get messier and grubbier as the film progresses: the first assassination is the kind of clean hit we might see in The Godfather, but the later killings become increasingly disturbing. Spielberg depicts them with the same unflinching eye that we saw in the more horrific moments of Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan.

Even seemingly straightforward expository scenes are expertly done. The opening account of the Munich siege, for example, is not as superficially spectacular as the more self-conscious set-pieces later in the film, but it is nevertheless amongst the most skilfully constructed sequences I’ve seen for a long time. Spielberg seamlessly blends a recreation of the actual events with genuine news footage from the time in a way that collapses the boundary between reality and fiction. This juxtaposition often occurs in the same shot, as when we see one of the terrorists step out onto a balcony deep in the frame, while in the foreground real footage of the same moment is playing on the television inside the apartment. This isn’t just a pointless technical flourish: by showing us the events at the Olympics largely through the eyes of the media, Spielberg shows the immediacy with which the shocking events were felt by the wider world. This in turn helps us to understand the depth of feeling that drove the Jewish response.

In depicting that response, and raising questions not only about its legitimacy, but also its effectiveness, Spielberg has created a storm of controversy. He has been attacked by both Jewish and Palestinian commentators for inaccuracies and perceived bias his depiction of events. Perhaps more interestingly, he has been criticised for so-called “moral equivalency:” suggesting that the intelligence operatives are as bad as the terrorists they target. This, it has been suggested, is an ethical cop-out that lets Spielberg avoid judging either side. Not all of this criticism can be easily dismissed: in particular, any fictionalised depiction of such sensitive real events raises all sorts of difficult ethical questions about responsibility to the truth, and these are almost impossible to unpick without a detailed knowledge of what actually happened. However, the “moral equivalency” charge seems to me misguided. It’s an accusation that seems to ask Spielberg to draw conclusions (and absolute ones at that), where to do so only entrenches both sides in their positions. Instead, Spielberg asks questions and starts a debate, in sharp contrast to the “dialogue” of escalating violence depicted in the film.

It has also been suggested that he paints an overly rosy picture of the Palestinain targets – several of whom are polite and likeable – but it seems to me only realistic to portray those who back the terrorist actions to be regular people rather than crazy fanatics. Rational and humane people support violent actions because they can construct intellectual defences of the righteousness of their cause, and are able to distance themselves from the human consequences of their positions. Munich shows how both sides articulate defences of their actions, but then strips these justifications away by showing the unfolding carnage that results from the use of violent means to achieve their objectives. The ultimate point of Munich is that violence simply leads to more violence, a point that is difficult to dispute in the context of the history of the Israeli / Palestinians conflict. The evocative final shot will be misunderstood by many as an attempt to draw a spurious link between the fallout from Munich and more recent events. Instead, as “Moriarty” from Ain’t It Cool (of all places) has pointed out, it is reminder that there is no true haven from terrorism while people attempt to right wrongs through violent actions. (A series of interesting articles discussing the film’s politics – including Spielberg’s own take – can be found at Roger Ebert’s site, here, here and here).

The danger of the film’s structure is that by following the violence inflicted by the Israelis, the havoc wrought by their Black September quarry would be forgotten. It’s understandable, then, that Spielberg chose to distribute flashbacks to the events of Munich throughout the film. Unfortunately, the device simply doesn’t work. I’m never a fan of the gradually expanding flashback as a narrative gimmick: unless the expansion is informed by the events in the main thread of the story (as in Errol Morris’ documentary The Thin Blue Line), it usually feels like an attempt to circumvent some sort of structural problem. In this case, the expanding flashback culminates in a clumsy montage that intercuts the final moments of the Munich stand-off with a sex scene between Avner and his wife. The sequence simply doesn’t work, and coming as late in the film as it does it deflates the impact of the film in its crucial concluding minutes. It’s the largest of the film’s faults: generally, the points that hold back Munich from greatness are little details here and there. Dialogue is occasionally overly-emphatic and unsubtle (“You think Israel is your mother,” declares Avner’s wife early on, as if she’s reading from the screenwriter’s character notes), and there are a few points that don’t make a great deal of sense. (In the assassination in the hotel, for example, why does Avner need to turn off the light, given what we have seen about the way the bomb is activated?)

In falling short of greatness, Munich falls squarely within the body of work Spielberg has produced in the new millennium. With the exception of the awful The Terminal, Spielberg’s post-2000 films have been uniformly solid without quite being masterpieces. As I argued in my career retrospective of Spielberg at Senses of Cinema, these recent films don’t quite have the precocious brilliance of his best early films. Yet they show Spielberg is willing to take risks and produce films that challenge both himself and audiences: for that, he should be admired.