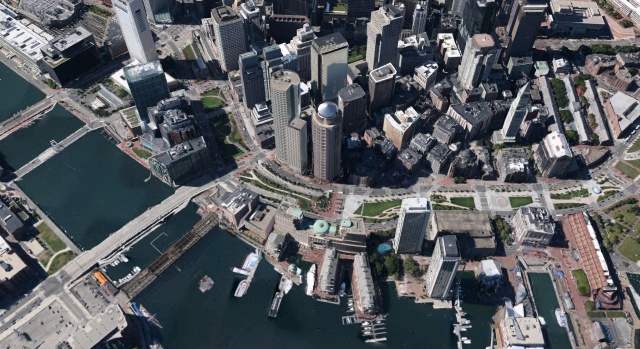

The image above isn’t an aerial photograph. It’s a screenshot of the new 3D view rolled out recently in the latest version of Google Earth for the newer iPads and iPhones. I gather it is available for their Android app too, although it is not yet available on the PC version. This is downtown Boston, one of the first few cities for which this imagery has been released; you can click to enlarge it to have a look at just how realistic the imagery is. If you have access to a device that supports these 3D maps, I suggest you give them a try. They’re amazing.

Google Earth has had 3D buildings for some time now, but previously they were constructed from individually built computer models sourced from various contributors, including an army of amateur hobbyists. As I write, that is still what you’ll see on Google Earth for PC. The buildings seen above, however, are built using “stereophotogrammetry:” essentially, Google use photographic data to not only capture the faces of the buildings, but also to create a 3D model of the cities’ geometry. The photographs are then mapped onto the model, allowing a near-photorealistic 3D virtual city to be manipulated in real time.