Hot on the heels (at least in the order I found out about them) of the restored Metropolis comes the news that Touch of Evil will get a new DVD release carrying three versions of the film. The current DVD features only a highly speculative “restoration,” which even the people who made it felt should not have replaced the earlier versions, as noted by Jonathan Rosenbaum:

I was a consultant on the third version–a re-edit by Walter Murch based on a memo written by Welles to Universal in the 50s–and it was never the intention of Murch, me, or our producer Rick Schmidlin to replace the film’s original release version or the longer preview version that supplanted it in the 70s. We were hoping that all three could be released in a DVD box set.

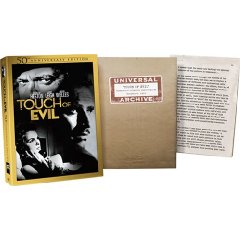

Well, now we have that set, correcting one of the worst bits of DVD butchery we’ve seen for a while. That’s sensational news. Click the image below to order it.