In 2017 the Victorian Auditor-General released a scathing report into the Victoria’s planning system.

It reported that:

Governments, state planning departments and councils have directed significant effort over many years to reform and improve the system. Despite this, they have not prioritised or implemented review and reform recommendations in a timely way, if at all. The assessments DELWP and councils provide to inform decisions are not as comprehensive as required by the Act and the VPP. DELWP and councils have also not measured the success of the system’s contribution to achieving planning policy objectives.

As a result, planning schemes remain overly complex. They are difficult to use and apply consistently to meet the intent of state planning objectives, and there is limited assurance that planning decisions deliver the net community benefit and sustainable outcomes that they should.[1]

Furthermore, it noted that “past reforms have had little impact on fixing other systemic problems impeding the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of planning schemes.”

Indeed, the Auditor-General had prepared a similar report in 2008, which made similar recommendations. In particular, the 2008 audit had recommended a comprehensive performance monitoring regime for the system. However the 2017 audit found few of these recommendations had been implemented.

That the Auditor-General had issued such a strong set of findings calling into account the stewardship of the system should have been a big story in the local planning profession. That it repeated so many of its 2008 findings, and found that the earlier audit had been largely ignored, should have caused some outrage. Yet the audit dropped with scarcely a whimper, quickly fading from attention.

Perhaps this was because help was at hand. After all, the government had announced it Smart Planning reforms. As the audit noted:

The state government has funded a $25.4 million overhaul of the planning system—the Smart Planning Program—that DELWP is delivering over the next two years. Specific projects, if implemented well, should address many of the key issues identified in this audit—delivering a streamlined state planning policy framework, model planning schemes, improved zones and overlays, and an improved electronic system for managing and sharing planning information.[2]

Clearly however, as the report noted, the detail of the reforms was crucial. After all, we had been here before. The 2008 audit had included assurances from the secretary of the Department that changes were underway to address the concerns, including a review of the Planning & Environment Act that had already been announced.[3]

Yet the reviews underway in 2008 obviously didn’t fix the issues. Indeed, I’d argue they did the opposite: the kind of muddling-along reviews that occurred back then are part of the problem. They became a mechanism for the Department to shrug off the implications of that audit, rather than to engage in some introspection about how the early to mid 2000s – in which we had a new-ish planning system, a new planning strategy, and relative political stability – had been such a period of drift for Victorian planning.

The presence of two audits with such similar findings means that we need to ask not just about the system fixes implied by the first. We also need to look beyond that at our problem-solving processes. Is our approach to system review sound? Are we diagnosing the problem correctly? And are we setting up our reform processes in a manner that gives them a realistic chance of succeeding?

VC148 – What Did it Do?

I want to dig into some of those meta-questions, but let’s start with a more constrained analysis just looking at the current Smart Planning changes from a simpler planning systems perspective. (After all, if the current reforms have nailed it, there’s arguably no need to look deeper).

The Smart Planning program released a discussion paper in late 2017 (about which I was not keen – see here and here) and its centrepiece amendment, VC148, dropped in late July. That has made a series of changes, some of the more significant being:

- Roll-out of a new “Integrated PPF,” in which the current SPPF and LPPF structure is replaced with a model where local clauses sit “behind” equivalent state clauses. This also includes the introduction of “regional” clauses which are selectively included only in relevant schemes.

- What the Departmnt call “a simpler VPP Structure with VicSmart built in.” This involves significant reorganisation of the VicSmart clauses, with key operative provisions distributed more through the core VPP clauses, rather than in a separate section at the back of the scheme.

- Restructured particular provisions, introducing some sense of structure to these parts of the scheme.

- Mandatory statements of significance in new heritage overlays.

- Lower “Column B” rates for car parking close to the Principal Public Transport Network (with, for example, the effect that in such locations there is no need for visitor car parking in residential development in these locations).

(You can read the Department’s own summary – which references a few other tidy-ups that I haven’t mentioned – here).

Some of these are really good ideas. The new structure for particular provisions is welcome, for example. The old clause 52 was random and hard to navigate; that problem won’t be completely eliminated, but giving three main subsections (cl 51 for area-based provisions; cl 52 for provisions requiring enabling or exempting permits; and 53 for general performance requirements) creates at least some structure. In practice, of course, plenty of provisions combine the role of both permit-triggering cl 52 provisions and the performance standards envisioned for cl 53; this I think limits the actual utility of the distinction somewhat. However some structure is better than no structure.

Other changes are fine but seem to avoid obvious opportunities to do more. Mandatory statements of significance for HOs seems like a logical change, though someone with more experience preparing heritage amendments could probably comment on whether it will actually change practice – are panels and DELWP really letting though new HOs without a statement of significance? Regardless, formalising such a requirement, and creating a specific spot for it to hang off in the VPP clause, seems good practice. My main observation about this is that it would have seemed simple enough to go further and create more fully customisable heritage overlay schedules.

Three of the above changes, however, are worth discussing in detail because they require some more explanation, and because they point to the larger deficiencies in the reform program.

Column B Rates for Parking Near the Principal Public Transport Network

I am not a fan of minimum parking requirements as a planning tool – to put it mildly – so at one level any winding back of their impact is welcome. The wider use of column B rates will reduce administrative burden, which will be great, especially in commercial areas. Visitor parking requirements for residential developments are especially egregious, as such parking is very often poorly utilised (visitors tend to park on-street), so in one sense I am happy to see them go.

The problem here is that this desirable outcome is being achieved by an illogical mechanism; and when that is done, the logic of the control tends to break down in contested situations. I say that because the PPTN maps that this change relies on are not an effective mapping of sites that are well-located in terms of public transport, as they don’t distinguish at all between quality of services. Near a low frequency bus route that doesn’t run in the evenings or on weekends? You’re on the map! Never mind that the bus doesn’t run at the actual times the visitors for whom you now don’t need to provide parking might use the service.

Again, as stated above, I don’t actually care about visitor parking. The logic problem here does matter, though, because the visitor parking has been waived on the basis that the scheme is saying sites on these maps are well-located. That means developers are now going to start using these maps as pointers to preferred locations for development, even though in practice many of these sites are not well serviced at all. That is going to exacerbate the existing problems in the General Residential Zone in particular, where system neglect and poorly designed controls have left the zone very vulnerable to poor outcomes.

It is true that PPTN mapping was already referenced in schemes; it is therefore technically correct to argue that aside from the visitor parking trigger the status of the PPTN maps hasn’t really changed. Yet this ignores the practical realities of how these things play out in contested situations such as VCAT hearings. In practice, the PPTN maps have now been given a greatly elevated status and visibility. That’s problematic when the maps are of such dubious merit as a tool for assessing access to transport.

The problem, then, is that this is a shortcut. The mapping isn’t fit-for-purpose, and hasn’t been properly reviewed to see if it works for this use case. Such shortcuts are a hallmark of our system reviews, usually done as a substitute for more difficult reform. (I’d argue that the column B rates are themselves just such a fiddle; they emerged from the 2004-2012 car parking review and were a substitute for the bolder review that was needed of the parking controls). Getting the right answer by the wrong logic tends to create unexpected and illogical outcomes, and I think that will happen here.

“A Simpler VPP Structure with VicSmart Built In”

This is the planning scheme equivalent of saying “I’ve heard you don’t like picking anchovies off your pizza, so good news – now they’re baked into the crust.”

It is true that if you keep VicSmart, it should be in individual clauses to avoid the fiendish cross-referencing the original implementation created. But VicSmart is, as I’ve written at length elsewhere before (including in my book), a legitimately terrible idea. It avoids genuine simplification and streamlining, and substitutes procedural complexity instead. The complexity was hidden before, but now pollutes every zone and overlay with a series of garbage provisions that clutter the controls but do nothing to actually help get simple applications off the books. It persists, presumably, because enough people high up in DELWP have repeatedly committed to the idea that they have to keep doubling, tripling, and quadrupling down on it.

In terms of process, the strange Departmental commitment to VicSmart I think stems from a failure to correctly diagnose problems; it is an output of the strange insistence that our system needs more “streaming,” which I discuss below.

Integrated PPF

The integrated PPF isn’t a bad idea, per se. However there are two main objections I have to the form in which it is being rolled out:

- It doesn’t clearly serve as a solution to the main issues with the policy framework.

- The sequencing of the roll-out of the integrated PPF is all wrong – it needs to come after a detailed review of Victorian drafting practice to ensure the potential benefits of the redraft are realised.

Taken together these factors mean that the chance for a serious improvement to the way the policy framework functions will be squandered. The integrated PPF will consume a significant amount of strategic resources over the coming few years, and will occur at the expense of simpler and more productive reforms. So while it may be a reasonable idea in an abstract sense, it is much less worthwhile if actually weighed against the cost of introducing it and the opportunity costs of alternative proposals not pursued.

To explain the first of the above objections, relating to the PPF’s alignment with the existing problems, let’s consider what issues the integrated PPF addresses. It seems to me it achieves two main things. Firstly, it introduces regional clauses, which means that certain state provisions that are only relevant in particular areas appear only in those particular schemes. Secondly, it should hopefully slim down schemes by ensuring local clauses don’t repeat state content, and instead focus on only those areas where the local scheme can add value.

On the first point, I am not sure I see any benefit from regional clauses. We don’t have regional authorities, so there’s no ownership of such clauses. They are just state clauses that only apply to certain areas. Removing region-specific state clauses reduces the theoretical size of a scheme, but almost nobody prints out schemes any more. Once schemes are accessed digitally, the number of pages simply doesn’t matter. What is important in a digitally accessed scheme is not length but navigability – i.e. being able to go straight to the relevant parts with minimal confusion – and that isn’t impacted upon by the presence or absence of particular region-specific clauses in a any given scheme.

I can, in fact, see two key problems with regional clauses being removed from select schemes. The first is that seeing policies that apply elsewhere can often be relevant in planning considerations. If I am assessing, say, a proposal for a major container port, it would be relevant to me that state policy for the next region over actually designates that as the preferred location for such a port. Similar points could be made about many aspects of policy such as settlement strategies and the like, where understanding the whole picture is important. I’m not sure that the benefits of reducing notional page numbers in an intangible digital scheme outweighs whatever issues of discoverability arise from omitting certain parts of the scheme from particular regions.

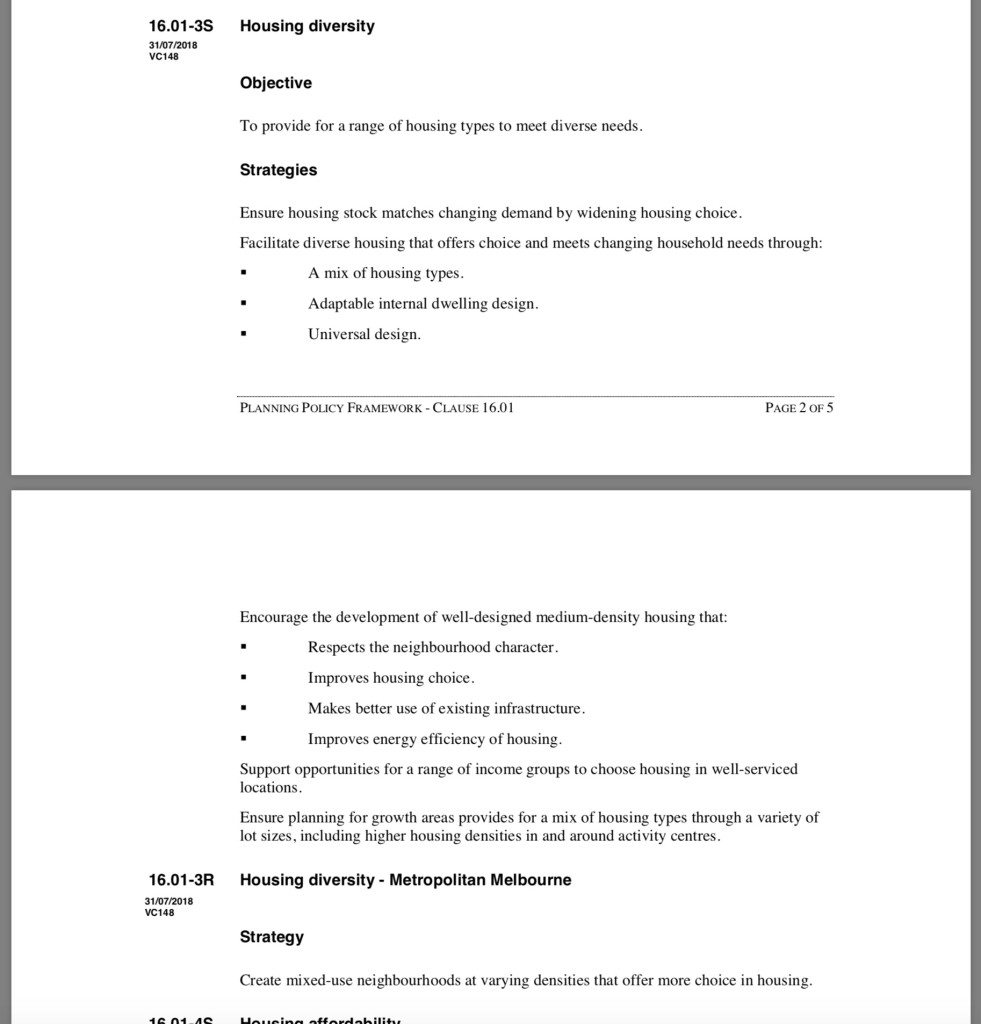

The second issue with regional clauses relates to the kind of drafting this structure encourages. I would argue that the three-tiered structure will actually encourage poor drafting, because of the temptation to create filler clauses of little dubious value for the extra tier. There are already many examples of this in the rollout version. Look at the clause for housing diversity below for a particularly egregious example.

Here, the additional layer just encourages a dumb “do that, but in this region” clause at 16.01-3R; there are slightly less obvious, but conceptually similar, examples throughout the new PPF. Now, it is possible that over time these clauses will get better content. But it seems to me likely that this structure will actually encourage the kind of tiered restatement of objectives at different layers that is already a feature of the system (something I talk about in relation to the existing system at page 107 of my book). This is critical, because when a restructure of a planning framework is truly content-neutral, looking at what the structure encourages becomes our main point of interest.

Putting aside the regional section and looking at the relationship between state and local sections, where this structure can achieve a benefit is in slimming down local sections of schemes. I gather that has been a key finding out of the pilot process, where councils found that by aligning their content with the integrated PPF they could remove content. That’s certainly a positive, although I’d have thought a good audit of local policy could actually strip out such content independent of structure (and this raises the issue of whether the “audit” process is being sequenced correctly, to which I will return in a moment).

The key issue in evaluating the PPF structure is what kind of drafting progression it encourages. The structure builds in an assumption that refinement of strategy occurs from state to local level. That’s true of certain kinds of policy – and activity centre policy is the classic example. So, for example, state policy says we want to encourage development near activity centres. Regional clauses can then refine that somewhat, which may or may not add value – you can form your own view as to how much value they are adding by looking at the metropolitan regional activity centre clause – and then local clauses fill in details such as local centre hierarchies. Putting aside my grousing about regional clauses, this is I think a best-fit example for the use of the PPF structure.

The problem is, not all policy refines spatially. I would argue just as prevalent – if not more so – is policy that needs to progress from overarching statements of intent to detailed application guidance. The old structure did that in the LPPF with clauses 21 (the MSS) and 12 (local policies), but not in its state section. This mean that many detailed bits of decision guidance – things like urban design policies, heritage policies, and the like – were left for councils to resolve in local policies, when they were actually better resolved state-wide. That to me was a more critical structural flaw, which is why I have long advocated for a cl 11 / 12 / 21 / 22 model (see here). The PPF structure, by contrast, entrenches the structural implication that all detailed policy resolution is for local councils to do. I don’t think that’s a helpful message.

The other question is whether the sequencing here is correct. As mentioned, a key advantage of this process is forcing a rewrite of local planning policies to streamline them. Yet we badly need a re-evaluation of statutory drafting practice in Victoria, and that discussion clearly should come first. There is, apparently, a revised drafting manual on its way. The November discussion paper, however, did not give much sense that there is a serious understanding in DELWP of the entrenched flaws in drafting culture in Victoria. Reshaping drafting practice should be a more inclusive and involved process that is subject to wider discussion, and that clearly should precede any state-wide local policy redraft.

VC148 – What Didn’t it Do?

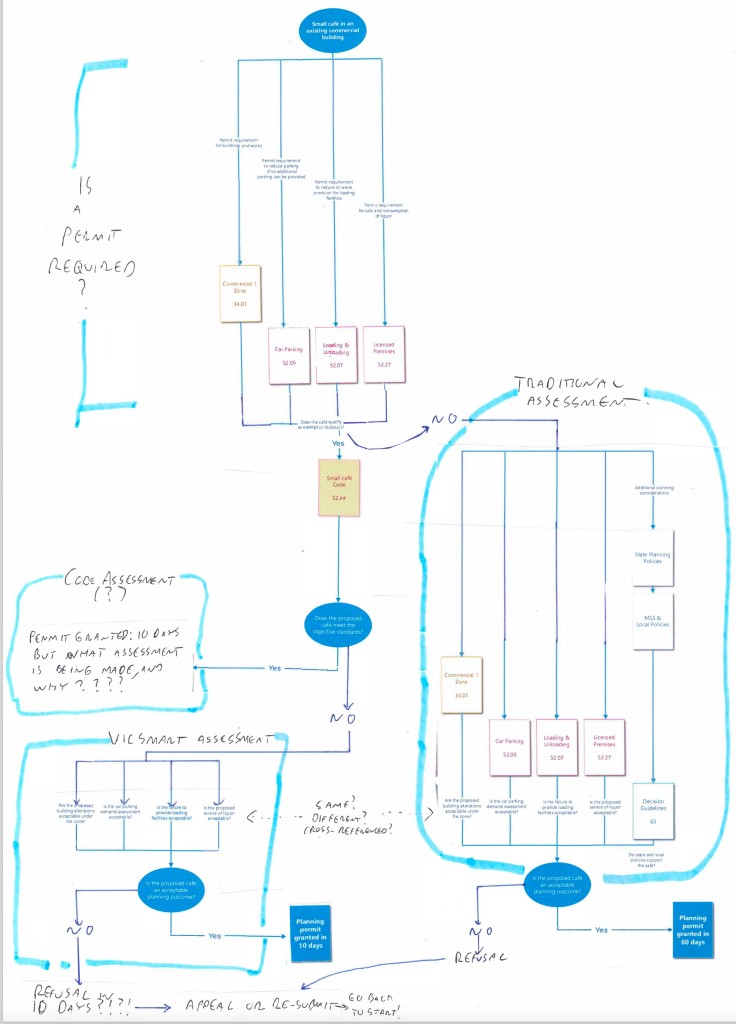

Before going further, it is worth just highlighting an important change VC148 didn’t make, which was to go further down the road of “code assessment.” As I argued last year, this would go even further down the VicSmart road of adding procedural complexity to the system, and would make the system much harder to maintain. This is because the system is not currently organised primarily around category-based clauses – adding such clauses or codes into our system then increases the amount of cross-referencing between the main issue-based clauses and the use-based codes, increasing the complexity of the system.

(Ironically, one tidy-up included in VC148 was to actually remove two old use-based particular provisions, in recognition that they had become neglected an out-of-date. This is exactly the kind of problem I warned of in my piece last year).

It isn’t clear whether this is because the idea of code assessment has been abandoned, or just held off for later. I hope for the former, but fear the latter. DELWP, however, have not explained their thinking on this point.

Smart Planning’s Lack of Diagnosis

Clearly I have a lot of doubts about the Smart Planning process. A recurring theme is that I can’t see the line between problem and solution. The integrated PPF seems to solve problems that I don’t think are that severe, and to ignore problems that I think are more urgent. The commitment to VicSmart, and the threat of an increase in code assessment, both seem like poor fits for our system. But where do they arise from?

The October 2017 Smart Planning paper includes familiar refrains about the problems with the system, with references to complexity and lack of clarity. Yet these sections are brief (a few paragraphs in the introduction and a two page discussion in an appendix) and frustratingly imprecise. They don’t show much sense about what exactly has driven complexity or imprecision. Is it the structure of schemes, and if so, what aspects of that structure? Is it the guidance about how they are drafted, and if so, what aspects of that are wrong? What’s the role of institutional culture (both in Victorian planning and in key bodies such as councils, DELWP, and panels)?

There simply isn’t enough precision in the diagnosis to track the identified problems through to the proposed solutions.

There also isn’t nearly enough detail about how the review draws on work already done. Key reforms are listed, but not analysed in any detail. In particular, there is no point-by-point response to the auditor-general’s findings, making it hard to justify the Department’s view that Smart Planning is a response. This also means that certain key findings – notably the need for more accountable system monitoring and review – recede from view. There are only brief references to the 2011 Underwood review. This is a critical omission, because that work – while not perfect – was the most open and thorough consultative review of the system undertaken since it inception.

A Key Mis-diagnosis: System Streaming and the DAF Model

While I have argued that generally the Smart Planning material suffers from a failure to draw clear links back to earlier reforms, and to specifically diagnose problems, one central theme from earlier rounds of reform is clear. This is the focus on “system streaming,” which essentially underpins both VicSmart and the idea of code assessment. (VicSmart arose as a failed attempt to implement a code assessment system). Here there is certainly a clear diagnosis – the view is that the system doesn’t scale correctly, applying a one-size fits all assessment model to all application types. And there is no doubt this flows from previous system reviews, with multiple previous rounds of reform having identified the system’s purported one-size-fits-all structure and proposing code assessment – and related legislative changes – as a response. This line of thinking can be traced back in particular to the 2005 Development Assessment Forum “Leading Practice” model (which I argue in my book is not a very helpful model to apply to the Victorian system).

In my view, the idea that Victorian system offers a one-size-fits-all model is the great structuring furphy of the last two decades of Victorian planning reform.

Our development assessment process is not one size fits all, and it is hard to say why people keep suggesting it is. Development can be approved by a planning permit process, or through the scheme amendment process (with or without public notice) using multiple different mechanisms. Or it can be approved through a combined scheme and amendment process. Or we can apply an environmental impact assessment process, which is almost completely open-ended in the kinds of assessment it allows for, and exists at both state and federal levels. And that’s before we get to dedicated facilitative legislation (such as the Major Project Facilitation Act) or the wider range of issue-specific approval mechanisms that exist outside of planning legislation.

Even at the mundane end of the spectrum, within a planning permit process, there is a great deal of variety. Notice requirements can be made mandatory, discretionary, or waived. Ditto with referral requirements (and we can also vary whether referral comments are binding on responsible authorities). Extent of delegation can be varied. Assessment tools vary greatly: they can be simple or complex; objective or subjective; performance-based or prescriptive; or mandatory or discretionary, amongst other possible variations.

(All of the above, incidentally, reflects the system even before VicSmart.)

This is not a one-size-fits-all model. As I argue in my book, the Victorian system can be understood as customisable using a series of system “switches” that can be set in different combinations. A system “stream” is just a set combination of these switches; building a system around certain pre-set streams – as advocated in the DAF paper – actually reduces the variability allowed in the system.

Similarly, code assessment is often advocated as a key system stream. But if by code assessment we mean “objective controls that, if complied with, mean no permit is required” then we already have the mechanism to do that in the VPPs. Multiple sets of existing controls – including controls about tennis courts, mobile phone towers, and home-based business – are already code assessment in this sense. The DAF paper’s emphasis on code assessment needs to be understood on the context of a national system where – particularly back in 2004 – other states were not as progressed in Victoria in implementing state-wide controls. But the basic mechanism of code assessment has existed in the VPPs from the start.

The strange insistence on trying to implement system streams and code assessment when equivalent or better tools already existed in our system has led to a great deal of wheel-spinning, and then, ultimately garbage provisions like VicSmart.

Where Does That Leave Us? (A Brief History of System Garbagification)

I have mentioned the Underwood review of 2011, which released a preliminary report but was then quietly abandoned. The failure to actually take that review forward seems, in retrospect, a turning point. It wasn’t perfect – it still talked about system streaming, for example, though it came closer than most to an epiphany on the issue of code assessment – but it represented the kind of thorough system diagnoses that needs to precede sensible reform.

Instead, however since 2012 we have seen an escalation of chaotic, illogical and reactive reform. VicSmart and now Smart Planning are key culprits, but they have been exacerbated by a number of other poorly justified and implemented changes, notably:

- Introduction and then removal of a maximum dwelling limit in the Neighbourhood Residential Zone.

- Extreme liberalisation commercial and industrial zones.

- Mandatory height limits in mid-tier residential zones.

- Garden area controls.

In addition, the sensible changes to the residential controls were introduced in this period, but then rolled out in a rushed manner ahead of the planning strategy that would have guided their application. They were also changed once applied, meaning that the controls and their strategic justification in many cases no longer aligned.

In combination, these changes have meant that since 2012, we have entered a depressing phase in which reform has actively made the system worse, as opposed to the mere atrophy that characterised the fifteen years preceding that. The system was clearer and more structurally sound in 2012 than it is today.

What Are The Problems? Part 1 – What Works

I have argued at some length that the issues with the system have been misdiagnosed. So what is wrong with the system, and what works well? Well, I have written a whole book on the topic, but let’s consider those points briefly, starting with what works. It is important to understand the strength of the system so that we don’t design in a way that cuts across these virtues.

Key virtues of the VPP system include:

- Standardisation of approach. The use of a common set of controls, and standard template for local controls, increases consistency between different planning schemes. This assists users of the system and also improves portability of skills for planners.

- Customisability of assessment pathways. The VPPs (in combination with the Planning & Environment Act 1987) allow customised assessment pathways through varying levels of referral, notice and appeal rights, as well as varying complexities of assessment tools.

- Issue-based controls. The VPP use an issues-based structure, where individual clauses (such as particular provisions or an overlay) typically outline whether a permit is required and contain the key guidelines for assessment. There are, however, exceptions to this, and the structure has complicated over time, as noted below.

- Policy integration. The use of state and local planning policy frameworks allow for decisions to draw on an integrated policy background as necessary.

To an extent aspects of VPP system design are balanced against each other. For example, some tension exists between the use of issues-based controls and policy integration, since an overly broad assessment that considers all aspects of policy may become unwieldy. At its best, however, the VPP system provides targeted issues-based controls that nevertheless allow consideration of a broader range of strategic objectives when necessary.

What Are The Problems? Part 2 – System Problems

Here’s roughly what I see as the key issues with the system.

System bloat and complication

When originally introduced the system “stripped back” a great deal of complexity from the array of local planning schemes. However the desire to standardise controls has always been balanced against the need for customised solutions for particular issues and local circumstance. Some complications were present from “day one” of the system due to translations of old schemes, and over time there has been a gradual accrual of new mechanisms, including heavily customisable zones (such as the Activity Centre Zones) and alternative assessment pathways (such as the VicSmart system).

Similarly, two decades of tinkering with individual controls within the VPP has increased the complexity of many clauses. Many changes have been made in an ad-hoc manner without considering the consistency of the overall functioning of the system. In some cases, use of localised controls has been relied upon as an alternative to fixing core VPP controls that required attention, further diversifying controls.

Many such changes are worthwhile. However there is a need to re-examine the clauses to see where some of this complexity can be stripped back, either because it is unnecessary, or because it can be achieved in a simpler manner.

Poor targeting

The VPPs were built on an assumption that decision-making should be policy-led and performance-based, rather than prescriptive and rule-based. This meant many controls were discretionary for a wide manner of matters. For example, more uses were placed in section 2 (requiring a permit) than in pre-VPP schemes, and many zones and overlays require a permit for all buildings and works, subject to only limited exemptions. This increased regulatory burden by triggering many applications for minor buildings and works.

A key priority therefore should be to more precisely target the controls to focus only on those matters where the planning process adds significant value or is needed to ensure appropriate outcomes.

Lack of clarity

The policy-led focus of the VPPs has been supported by an approach to drafting of provisions that favoured the description of competing policy objectives, with the resolution of those objectives left to the planning permit in application process. This, combined with the use of highly discretionary controls and limited tools for spatially resolving planning dilemmas, has led to excessive uncertainty in the planning process.

Poor navigability and excessive cross-referencing

The broad nature of many permit triggers in the VPPs, and the use of schedules and overlays, means the system has become heavily dependent on the addition of exemption clauses to limit the application of clauses. This means that the operation of many provisions is driven by complex interaction between core provisions, their schedules, and exemption clauses (notably clause 62). This interaction was complicated further by the addition of the VicSmart system in 2013. VC148 partially corrects that by moving VicSmart back into the main clauses, as mentioned above, but that unfortunately then just complicates the main provisions.

What Are the Problems? Part 3 – Process and Culture Problems

As I noted at the outset, we have been through processes like this before. The response to the 2008 audit did not carefully respond to its findings, and ultimately fizzled out; the more rigorous and systematic Underwood review got off to a good start but was not seen through to completion. The Smart Planning process shows every sign of repeating those mistakes. As I have argued, it is a grab-bag of initiatives without a persuasive explanation having been provided for why they are the answer. This has meant that it perpetuates dubious solutions such as VicSmart that cut against the established design of the system and hence increase system complexity; and other ideas such as the integrated PPF that seem like solutions to second-order problems. It has also embraced an extremely complex set of solutions that are very hard to implement.

It is important to ask why our reform process delivers such poor outcomes. In my view, Smart Planning embodies several process and cultural problems that we need to resolve if we are to get better outcomes form these processes.

Firstly, planning reform needs to start talking about culture. This starts with owning and discussing issues with stewardship of the system. Both the 2008 and 2017 Auditor-General reports paint a picture of a system where stewardship has fundamentally broken down, but Departmental system reviews – even those, like Smart Planning, run with significant input from outside consultants – have not proven capable of seriously addressing this issue. We need reform to acknowledge these difficulties and put systems in place that actually make the Department more accountable in its monitoring roles. The 2008 Auditor-General report had a series of excellent and still largely-ignored recommendations for Departmental performance monitoring that would be an excellent starting point in this regard.

That discussion of culture also needs to acknowledge the broken relationship with local government. Local councils are the Department’s key partners in running the planning system; they are also the actual experts in day-to-day system function. Yet neither the daily management of the system nor the reform process reflect that. Councils are not empowered in suggesting or championing change, and the tone of reform documents does little to imply any kind of partnership with, or empowerment of, local councils. The increasing politicisation of the public sector has weakened the culture around consultation, with key changes increasingly kept secret until a “surprise, suckers!” announcement. The kind of detailed strategic justification and wide consultation that characterised earlier review processes is largely forgotten.

The Smart Planning Review was also set up in a way that inevitably compromised its outcomes. It was given only a short time to deliver, and was contingent upon a budget allocation that required an infusion of outside consultants to deliver upon the brief. I’m not opposed to outside consultants on such a review in principle – they can potentially serve a valuable culture-busting role, if nothing else – but this structure created an inevitable rush to a big blockbuster amendment in VC148.

This has compromised the development of the roadmap of reform. Firstly, it meant that the initial diagnosis phase was rushed. Instead of carefully working out what to do, and either doing fresh consultation or preparing a set of recommendations based on earlier work such as the Underwood review, Smart Planning was conceived form the start with a set of pre-existing initiatives. These seem to have particularly prioritised on things that were half done (the PPF) or which extended earlier work (VicSmart), rather than actually setting a coherent program of action. The timeframes for the process then did not allow sufficient time to genuinely review or consult on those initiatives.

I engaged early on with the Smart Planning team as it seemed that what they were suggesting was more complex than necessary and likely to be counter-productive; I pitched a fairly detailed set of alternate proposals to them. What was disappointing about this process was not even so much that such ideas were not taken on board. The problem was that it was clear they couldn’t be. It didn’t matter whether, say, the structure for the policy framework I have advocated for is better or worse than the PPF. There was just no scope in this review process to consider alternate paths.

Reforming Reform: Imagining a Better System Reform Process

Given the way the Smart Planning process has unfolded thus far, I am not optimistic about the realistic prospects for a change of direction. But if we want to avoid a repeat of the post-2008 audit scenario, we need a different approach to that currently being pursued by Smart Planning.

That involves de-schackling ourselves from the blockbuster reform package model. Stop hiring in teams of consultants. As argued above, such limited-time contracts set us up for rushed processes, and the risk of mistakes that come with big dramatic structural change. These include both drafting issues, and the kind of IT and change-management disasters that accompanied VC148.

The lure of blockbuster, marketable reform also has a tendency to lead us towards the false hope of releasing a big sexy package with a marketable name. It is much more alluring to announce a cool-sounding new system or stream than to focus on the meat-and-potatoes work of simple system tidy-ups. This is, I think, a big part of why VicSmart and code assessment have loomed as the recurring themes of successive waves of reform, despite the VPP system already including perfectly adequate mechanisms to implement objective codes and to customise assessment processes. If you point this out, though, the job of reform veers back into the boring business of drafting better planning provisions. Successive governments have therefore clung to the idea of sexy and marketable deliverables like VicSmart, even as they clutter and complicate the system.

We can get out of this cycle of counterproductive reform if a government is brave enough to scrap Smart Planning in its current form and go back to basics. That involves stopping and working out – in consultation with the industry and community, and drawing on the extensive work already done – a coherent roadmap that can be traced properly back to a diagnosis.

I have made my own attempt at outlining such a plan of works – see my post about that from March 2017. The idea here is to focus on reforms that are:

- Simple and contained – they avoid blockbuster changes as much as possible. They should be very achievable as Departmental core business.

- Directly responsive to a careful statement of the problems they are trying to solve.

- Easy to implement, but achieving incremental improvement straight away. For example, the “flipped overlays” I advocate can be implemented for new overlays immediately, with a measured conversion process for existing controls. This reduces the risk of avderse outcomes.

- Empowering to local government. Rather than punitive measures such as VicSmart, give councils the power to design their own controls, and then use this as a basis for controls that can be used everywhere.

Planning reform isn’t as hard as Smart Planning has made it. We do, however, need to change direction. We have big planning problems to solve, and we can’t waste another decade waiting for the Auditor-General to once again point out that we haven’t done the job.

Notes

[1]Victorian Auditor-General, “Managing Victoria’s System for Land Use and Development” (Victorian Government, March 2017), ix.

[2]Victorian Auditor-General, xi.

[3]Victorian Auditor-General, “Victoria’s Planning Framework for Land Use and Development” (Victorian Government, May 2008), 12.