This article is a belated posting of an article that first appeared in the October 2019 VPELA Revue. It is based on the talk I gave at the 2019 VPELA state conference.

What happened to Victorian planning in the 2000s?

It was a heady time. We had a long period of political stability a state level with the Bracks / Brumby government seeing out (almost) the entire decade. We had a brand-new planning system, with the VPPs having been introduced in the late 1990s and implemented by the early parts of the 2000s. And as of 2002 we had a new planning strategy in Melbourne 2030. This was a “no excuses” environment for urban planners.

Yet we didn’t get much done. The planning system wasn’t able, for example, to do much in the way of driving core Melbourne 2030 objectives such as intensifying housing close to transport and activity centres. By 2007 the implementation of Melbourne 2030 was subject to a critical audit, and in the latter years of the Bracks / Brumby government it had been informally deprecated. The system seemed as complex and burdensome as ever.

The reasons for those failures are complex and cannot be fully explored here. For now, I want to focus on the role of the VPP system itself. On the face of it, the VPP system’s (relative) failure is puzzling. There is a logic and rigour to the system’s design that is compelling. Why hasn’t it worked better?

Many of the reviews since – culminating in the Smart Planning reforms – have argued that only minor adjustments are needed. We have therefore spent much of the last two decades adding various bolt-ons and implementation tweaks to the system (notably VicSmart, three speed zones, and the integrated PPF), while chasing a few other white whales that are presumed to be the magic answer (notably system streaming and code assessment).

My view is that even the best of these initiatives have tended to focus on treatment of symptoms rather than underlying causes. (The worst, such as VicSmart, have cut unhelpfully across the grain of the system’s design and exacerbated the problems they were supposed to solve). I believe we need to better diagnose our problems, and be more targeted in our system fixes. That requires more examination of some of the system’s founding assumptions than has generally occurred thus far.

The VPP system is built on a foundational idea that seems compelling, and which therefore has remained under-unexamined. It is a paradigm that we can think of as a strategy-based discretion model and it married two impulses existing in parallel in 1990s planning.

The first was a deregulatory push, born from the neoliberal impulses common to governments worldwide since the 1980s, but particularly strongly championed by the Kennett government that had initiated the VPP reforms. This was an approach to planning that was suspicious of the perceived inflexibility of arbitrary and prescriptive rules. In this view, planners were – if not just dismissed as an annoyance – best conceived as development facilitators, a conception already embedded in the 1980s re-write of the planning legislation. “BOO” to regulation; “HOORAY” to facilitation and flexibility!

At the same time, from inside the planning profession, there was a thirst for more strategy-driven planning. This shared the neoliberal suspicion of prescriptive, rule-based planning; but this time the concern was that such approaches reduced the development assessment process to a bureaucratic tick-the-box exercise. Surely, this thinking went, it would be better to encourage more strategy-driven decision-making at the point of decision-making.

The strategy-based discretion model encouraged by these twin impulses is familiar. The VPPs – especially early on – focussed on highly discretionary controls, with decisions then driven by reference to a policy framework embedded in each scheme (the SPPF and LPPF, and going forward, the new integrated PPF). Theoretically this empowered decision-makers and led them to be more facilitative and strategy-driven.

Why, then, did the system lead to an escalation of workloads and a lack of concrete outcomes? I would argue that the problem is not so much design details of the system, as has often been argued, but rather a few fundamental problems with this founding paradigm.

Firstly, the idea of planners as facilitators was suspect from the start. Planners are regulators. Our job is to intervene in the process of land use development to achieve environmental, social and community outcomes that would not be achieved by individual actions, or the free operation of the market.

This is an inherently restrictive role. We don’t facilitate use or development – our applicants don’t need our help to build their buildings or open their businesses! Rather, we put boundaries around what they can do, and impose requirements upon them, to achieve policy outcomes. The individual burden of the requirements must then be balanced against the benefit of the policy outcomes. Our compact with the community, then, should be that we maximise our impact (policy outcomes) while minimising our footprint (regulatory burden and interference in private property rights).

Properly understood, this regulatory framing of planning should not worry developers or development-oriented consultants. Indeed, I would argue that a planner who thinks they are a facilitator is much more likely to be overly interventionist than one who sees themselves as a small footprint, high-impact regulator.

Planners’ reluctance to see ourselves as regulators speaks to the deep entrenchment of a certain conception of what regulators do. We should question those assumptions and understand what the regulatory conception of planning does not mean. It doesn’t mean planners should not be creative, strategic, customer-focussed, proactive, nimble, or even – yes – facilitative. But those adjectives speak to how we go about our role; we shouldn’t let the desire to frame our activity in more superficially positive terms confuse us about what our role actually is.

The second fundamental problem is how the strategy-based discretion model translates into action. Because this approach depends on strategic analysis at the decision-making stage, it requires many decisions to act upon. The VPP system, for example, increased the range of Section 2 uses in zones, and defaulted to wide “all buildings and works need a permit” triggers even in locations such as commercial and industrial zones. This maximised the footprint of the system.

At the same time, the assumption that decisions would be strategically driven placed too much onus on decision-makers to resolve competing policy provisions at application stage. This tendency was then exacerbated by the deregulatory impulse, which discouraged binding rules and policy specificity (the latter somehow having been thrown out with the bathwater of prescriptive rule-based planning). This led to vague and toothless policy, minimising policy impact.

This is, then, a high footprint, low impact model – precisely the opposite of what planning should be aiming for.

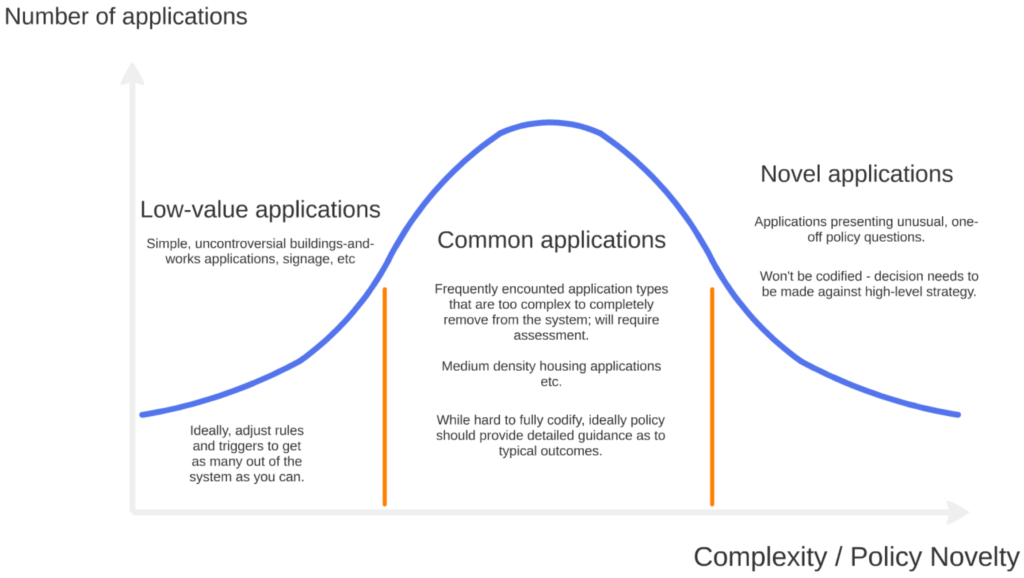

The third issue relates to what the system is best tuned to achieve. I think it is helpful to consider a planning system as accommodating three basic types of application. We can categorise these in terms of escalating complexity and policy novelty roughly as follows:

- Low-value applications. These are applications requiring little if any actual assessment – simple, uncontroversial buildings-and-works applications. They are, essentially, applications we don’t want to see. Ideally, we would adjust our planning system to remove as many of these from the system as we could.

- Common applications. These are frequently encountered application types. They are too complex for us to set codified rules that can get them out of the system, and they will therefore require assessment through a permit process. In Victoria, medium density housing applications are the classic example of such applications. They are, however, familiar enough application types that planning policy should be able to set quite clear guidance as to typical outcomes.

- Novel applications. These are applications presenting unusual, one-off or unforeseen policy questions. Decisions will need to be made on a first-principles, strategy-driven basis.

The Victorian strategy-based discretion model is tuned for the last of these categories at the expense of the other types. For the low-value applications, the breadth of discretion under the Victorian model leaves far too many applications in the system, creating an administrative drag that increases regulatory burden and hinders the ability of decision-makers to focus on more valuable applications. Meanwhile, the reluctance to resolve policy into clear guidance means the system is not clear enough about how common applications should typically be resolved. This leaves decision-makers (and applicants, and objectors) relitigating familiar issues through countless repeated applications.

This latter problem is exacerbated by excessive faith in the statement of policy in schemes as a form of implementation. A quirk of the theoretically laudable embedding of a policy framework in schemes is the too-prevalent view that simply stating a preference in policy is the regulatory implementation. This kind of wishing-well planning leaves planning strategy stating that high-level objectives will be “encouraged” or “facilitated,” neglecting the crucial step of implementing regulatory settings that will actually tangibly shift the on-the-ground situation.

We need to shift from the strategy-based discretion model to what we can consider a top-to-bottom model. This is a model that preserves the current system’s admirable focus on a clear strategic underpinning, but which frames policy responses in clear regulatory terms wherever possible.

It is a tribute to the robustness of the actual planning framework provided by the VPPs that a top-to-bottom model is relatively easily reconciled with the current mechanics of the system. A shift to top-to-bottom planning requires a shift of paradigm and rationale, supported by relatively minor system changes, rather than fundamental system restructure. It does, however, require a shift in the current Smart Planning agenda, which is currently ill-focussed and frequently misdirected.

It is not possible to fully outline such an alternate reform model in the space available here. Briefly, however, a top-to-bottom model involves:

- Much more precise targeting of controls. In particular, the opt-in bias of current overlay structures needs to be reversed.

- More sophisticated use of a range of regulatory levers. This will require far more nuanced guidance about when to use particular regulatory options, and more emphasis on fit-for-purpose system design, rather than dogmatic adherence to particular drafting approaches or system tools.

- Clear performance monitoring (including of policy efficacy, rather than just efficiency / throughput) to ensure that planning interventions deliver policy value and minimise burden.

- Structured stakeholder feedback to ensure an accountable relationship between those managing the system settings at state government, and those overwhelmingly running the system at local government.

- A thorough regulatory audit of the VPPs to ensure regulatory settings accord with the current policy objectives. This should focus both on legacy issues with outdated regulatory settings (such as car parking) as well as current policy priorities with weak or mis-set regulatory controls (such as activity-centre planning, affordable housing, and environmentally sustainable design).

The great paradox of system reform in Victoria is that our problems are at once deep-seated, and yet easily soluble. The VPPs still can provide an excellent delivery mechanism for planning policy if we properly diagnose where they have fallen short and fix those problems. If, by contrast, we continue on our current haphazard path, we risk a further decade or more of high footprint, low impact planning. The challenges in front of us are too big for us to accept that outcome.

This article has been updated from the original to use the term “strategy-based discretion” (which I adopted in the second edition of my book about the system). The original article used the phrase “policy-led discretion” for the same idea; I changed the term I used while rewriting my book just because the word “policy” has such a specific connotation in a scheme context. Note the book also develops the “top-to-bottom” idea further under the umbrella of “strategy-based regulation”, but I have kept the term unchanged in this article as the terms are not as directly equivalent.