Neighbourhood character is a clear example of an issue which cannot be reduced to simple rules. It requires qualitative assessment and the exercise of judgement. Similarly drafting a prescriptive standard to achieve objectives of building articulation to reduce bulk has proved unsuccessful. The focus of assessment of development proposals should always be on outcomes, not the satisfaction of rules for their own sake.

ResCode 2000: Part 1 Report – December 2000

The new DELWP paper Improving the Operation of ResCode: A New Model for Assessment -open for consultation here until next week – is presented as a streamlining of a cumbersome set of existing controls. It presents the alluring possibility of a world in which residential development standards set a fully objective baseline, and the kind of discretionary assessment currently applied to residential development is essentially only required when those standards are varied.

The premise is understandable – the ResCode controls are complex to administer (whether they are disproportionately complex is a different question, to which I shall return). The lure of efficiencies to be achieved with a truly objective baseline for assessment – especially when paired with not-yet-existing-but-foreseeable digital tools that would automate the initial compliance screening – is compelling.

But the paper presents a shortcut. It assumes the current controls can be modified into such objective standards without a rethink – indeed, it wrongly suggests that what is proposed is more-or-less just clarifying the controls so that they worked as intended.

The problem, though, is that the paper underestimates the role that the flexibility and discretion built into the current controls currently play. It suggests a streamlining of controls without doing the additional regulatory design work that would make this feasible. It therefore removes the aspects of ResCode that currently work to achieve acceptable outcomes, without adding back in sufficient mechanisms to take their place.

Its model therefore sidelines the critical role that context and character currently play in shaping residential development assessments. It would sweep aside council’s local housing and character policies for huge numbers of proposals. The distinctions between the three main residential zones would be dramatically reduced. Overall, development outcomes would become much more intense, especially in the Neighbourhood Residential and General Residential Zones.

It is, in short, a much more radical model than the paper implies.

How Were the ResCode Controls Designed to be Used?

In order to understand why the proposal is more far-reaching than it at first appears (and perhaps more radical than its authors intended or realised) it is necessary to go over some basics of how ResCode works. The following will be familiar territory to some readers, but needs to be recounted because (strange is it may seem for such a core part of our planning system) the way that ResCode works has become needlessly obscured over the last two decades – a confusion to which the paper unfortunately contributes.

The paper includes, as part of its background discussion, a description of how the control currently works that misdescribes how ResCode was designed to be used. It starts uncontroversially enough, with a description of the way the control lays out Objectives and Standards, but then turns (at page 28) to a description of “problems with the operation of ResCode.” Here it notes:

Over time, uncertainty about the proper operation of the ResCode standards and how they relate to the objectives has arisen. In particular, the relevance of the decision guidelines in circumstances where a standard is met has been the subject of a number of significant and well discussed determinations at VCAT. These include differing views about whether compliance with standards will be deemed to comply with objectives.

It then runs through several cases about the “deemed-to-comply” question, where the Tribunal wrestled with the implications of the wording of the “Operation” clause in ResCode provisions, before concluding:

The consequence of these conflicting interpretations of the operation of ResCode is that circumstances can arise where a residential development proposal may comply with a standard but is rejected because it is not deemed to meet the relevant objective having regard to the decision guidelines. Because ResCode requires that a development must meet all the objectives that apply to the application, this means that a permit cannot be granted.

These passages are deeply misleading. They obscure the reasons that doubt exists about the operation of the controls, and paint the correct interpretation of the controls as an undesirable product of confusion.

The way ResCode is supposed to work is not a mystery. An application must meet all the Objectives to be approved. The Standards (and for that matter the decision guidelines) should be used inform that judgement, but are secondary to the Objectives. At the end of the day it is compliance with the Objectives that is supposed to be assessed.

It is true that confusion has arisen, in that some VCAT decisions have held that meeting a Standard means that, by definition, the Objective is met. In this reading, for those Standards that are purely quantitative and measurable, this would mean that the Objective (and the Decision Guidelines) is only truly considered if a Standard is varied. That reading therefore effectively reverses the primacy of Objective and Standard – while theoretically a planner is assessing all Objectives, in practice for Objectives with quantitative Standards, the planner would only be able to make an assessment if the Standard is varied.

This confusion is a product of mistakes made when the controls were drafted – specifically, the wording of one sentence in the “Operation” section of each clause, which says the following about Standards:

Standards. A standard contains the requirements to meet the objective.

It is this sentence that has been held by some Tribunal members as creating deemed-to-comply Standards . While opinions may vary on that legal point1, there is no doubt that this reading of Standards is not the intended operation.

This point has been allowed to become contentious, and a source of confusion, by continued failure to provide clarification or to remedy that sentence in the Operation clause. But the original thinking was well-documented, as we pointed out in several editorials in the Victorian Planning Reports (most fully at VCAT Volume 3 Number 3, from September 2015).2

There is an extended discussion of how standards should work in the reports of the Advisory Committees that fed into the drafting of the code. In particular, there is an extended commentary at Section 3.2.1 of the Review of the Good Design Guide and VicCode 1 Advisory Committee report (from March 2000) that concludes:

The Standing Advisory Committee considers the time has come to abandon the last vestiges of the role of standards as deemed-to-comply provisions. It believes that any assumption that compliance with standards will meet relevant objectives and criteria should be removed from the new Residential Code… They are guidelines to decision-making but they never override the primacy of objectives [from section 3.2.2 – pages are unnumbered]

It continued:

Notwithstanding this experience, there is an expectation by some people that the quality of developments can be improved by the mechanistic application of controls. The Standing Advisory Committee considers that no matter how well-intentioned such controls are, situations will always arise where they will produce anomalous results. The issue is somewhat akin to mandatory sentencing. In the Committee’s opinion, the community at large does not wish the capacity for the exercise of judgement to be removed from the assessment of new residential development in established urban areas. Indeed, it wishes that capacity for judgement to be extended so that compliance with techniques, for instance, is not given more weight than whether objectives have been met and whether the development is appropriate in all the circumstances.

The certainty that the community is looking for can be provided by more guidance being given about what is expected in different circumstances. However, it is ‘guidance’ that is being sought, which retains the capacity for judgement and flexibility, not rigidity. For these reasons, the Standing Advisory Committee considers that the model for the structure of the new Residential Code, which it has suggested, will provide a framework for greater levels of guidance and greater certainty about what is expected in different locations. At the same time, in moving away from the concept of deemed-to-comply provisions, and regarding standards as guidelines within a policy, it offers the opportunity to give much greater weight to matters such as neighbourhood character. [Section 3.5 – emphasis in original]

The ResCode 2000: Part 1 Report, from December of the same year, makes similar comments, though is largely preoccupied with the inverse scenario: in other words, whether Standards should operate as mandatory minimum requirements (where non-compliance mandated refusal). This was in response to the mid-2000 consultation draft of ResCode that had included increased use of prescriptive Standards. In rejecting this approach this report affirmed the view of the earlier report:

Rather than removing the need for judgement and greater reliance on prescriptive deemed to comply requirements, the Standing Advisory Committee advocated moving away from the concept of deemed to comply provisions. It was suggested at pages 42 and 43 its final report that the certainty that the community is looking for can be provided by more guidance being given about what is expected in different circumstances which offers the opportunity for greater weight to be given to matters such as neighbourhood character.

The Committee agrees with submissions that the complex nature of meaningful assessment of proposals cannot be distilled down to a series of quantifiable requirements which do not require the exercise of judgement. Neighbourhood character is a clear example of an issue which cannot be reduced to simple rules. It requires qualitative assessment and the exercise of judgement. Similarly drafting a prescriptive standard to achieve objectives of building articulation to reduce bulk has proved unsuccessful. The focus of assessment of development proposals should always be on outcomes, not the satisfaction of rules for their own sake. [Section 3.2, subsection iii]

The latter Advisory Committee recommended abandonment of the 2000 draft and a reworked code. The terms it outlined for that redrafted code closely resemble the version of ResCode that ultimately emerged in August 2001.

It is possible that the Advisory Committees’ conclusions were rejected by the Department and State government when ResCode was introduced. If this is the case, however, they seem to have been unaware of having made that decision. The Practice Note Assessing a Planning Application for a Dwelling in a Residential Zone, issued in December 2001, took the same approach as those Advisory Committees, stating:

A standard contains the preferred measures to meet the objective. A standard should be met if this will meet the objective. However, if the particular features of the site or the neighbourhood mean that the standard would not meet the objective, an alternative design solution that meets the objective should be required. Remember that it is the objective that is being sought to be met, not the standard.

This remained the guidance until June 2014, when the equivalent Practice Note was amended, without explanation, to remove the latter parts of this passage.

Any argument that it was the intention that Standards be deemed-to-comply runs counter to all the explanation of how the code should work in the lead-up to its introduction; the clear admission of the relevant Advisory Committees that they hadn’t been able to frame appropriate deemed-to-comply rules to address character and bulk; the understanding when the quantitative rules were set of how they would operate; the guidance issued by the Department immediately after the code was introduced; and a decade of Departmental guidance after that.

It seems far more likely that the ambiguous wording of the Operation clause was, in fact, simply a mistake.

The “uncertainty about the proper operation of the ResCode standards and how they relate to the objectives” that the current paper refers to was, and remains, a matter for DELWP to clarify. The “differing views about whether compliance with standards will be deemed to comply with objectives” should be resolved by DELWP by restoring the guidance on this point and amending the Operation clause to work as intended. This could be done in very short order with a revised Practice Note followed by a routine fix-up VC amendment.

Unfortunately, rather than this simple clarification, the current paper has buried this remedy in a reform process that may or may not progress. It also further intensifies the exact confusion that it laments. As quoted above, it says “circumstances can arise where a residential development proposal may comply with a standard but is rejected because it is not deemed to meet the relevant objective having regard to the decision guidelines.” This is presented as “consequence of… conflicting interpretations” of the controls.

That is incorrect. This situation is not the product of those interpretations. Refusal of applications that fail to meet all the Objectives is the correct operation of the control. And the control has been applied that way in spite of, rather than because of, the confusion that has been allowed to arise by the failure to fix the Operation clause.

This is, of course, basic performance-based planning. ResCode was a culmination of more than a decade of moving residential controls away from what Minister for Planning Robert Maclellan disparaged (in his introduction to VicCode 2 in 1993) as the “arbitrary rules” that characterised older residential codes. It should not surprise us that a scheme control for an application type as complex as medium density housing requires the use of judgement and discretion.

Okay, Intent Aside, How is ResCode Actually Used?

One response I have heard to the above argument is that while it is perhaps true in theory, the “deemed-to-comply” approach has now taken root and represents the reality of current practice.

I think there are three main responses to this argument.

The first is to simply note that this isn’t how it works. A long delay fixing a drafting error is not strategic justification. Proponents of a change to the design of ResCode into a deemed-to-comply control need to mount that argument on merits, not rely on some kind of regulatory squatter’s rights.

Second, the “deemed-to-comply” approach isn’t prevailing in day-to-day practice. A few years ago I feared that it would, but in my experience the acceptance of this approach has receded in recent years. The firmest declarations of a deemed-to-comply approach were a series of decisions by one Tribunal Member, and it is some time since I have seen a VCAT decision explicitly endorse this approach. The most recent decision I am aware of discussing the issue is 16 Taylor Pty Ltd v Nillumbik SC [2020] VCAT 673, which rejected the deemed-to-comply approach.

Interestingly, this isn’t clearly acknowledged in the DELWP paper, despite it not citing a decision supporting a deemed-to-comply approach from any more recent than 2015.3 And while any account of what is happening in hearings will inevitably be anecdotal, in my own experience it is some time since I have heard an advocate before the Tribunal lean wholeheartedly on “if it meets the Standard it meets the Objective” as a rationale for approval – presumably because such clear embrace of a minimum compliance approach doesn’t help to paint the picture of a site-responsive design that, at the moment, is still a key tenet of the controls.

Third, even if the deemed-to-comply approach is fully accepted, a decision-maker is still able to draw on the broader general discretion created by the framing of the zone, local policy, and the Neighbourhood Character objective in ResCode. These allow considerable scope for discretionary consideration. In reality, this has been the key workaround used by decision-makers to keep applying discretionary decision-making even when the deemed-to-comply approach was accepted. This workaround is not ideal, as it creates muddy, logically inconsistent decision-making (with, for example, a decision-maker deciding a site coverage doesn’t accord with neighbourhood character policy or the Neighbourhood Character objective despite it being deemed to have met a Site Coverage objective framed in character terms). But it does still stake ground for individual context in the thought process of decision-makers.

The confusion caused by the drafting error in the Operation clause has not, therefore, made ResCode fully deemed-to-comply. I think it has contributed to a general intensification of outcomes, because it has somewhat diluted the role of context and character and raised some doubt about the ability of councils to refuse standard-compliant development. The general lack of clarity has also contributed to disputes during the process which has increased the system delays that the current paper now seeks to resolve.

However it has not swept away discretionary consideration of Objectives to the point where Standards are used in a deemed-to-comply manner. It is therefore incorrect to suggest that using the Standards in such a way would be either consistent with, or only a minor change to, existing usage.

A final point to be made about the current operation of ResCode is that decisions are also informed by local policy. While the role of policy has been progressively undermined since (ironically) the 2007 Making Local Policy Stronger review, local policy remains a useful and vital tool. We are in the latter stages of a several-year process of reviewing and restructuring local policies into a new framework, which presumably has to be understood as an investment in maintaining their use in the system.

It is true that local policies have often been poorly written, but they are a core element of the VPP system. They play a vital role in guiding localised outcomes under ResCode – which, after all, provides the same standards across all zones and areas and therefore will not (without the imposition of some other guidance or discretionary judgement) reflect particular local contexts.

The Importance of Context and Character: ResCode Properly Used

It is hopefully clear that under the framework described above, ResCode Standards are not an indication of a universally acceptable outcome.

Instead they are what we can call a benchmark, an indication of a typically acceptable outcome. They are a starting point that means the discussion is not completely unmoored from any reference point, but as the original ResCode guidance makes clear, the judgement ultimately to be made is if the Objective is met. Informing that judgement, the decision-maker should be looking at the local context and character to determine whether a requirement that is more or less than the standard is warranted in a particular case. This is why applicants have to prepare a Neighbourhood and Site Description and Design Response.

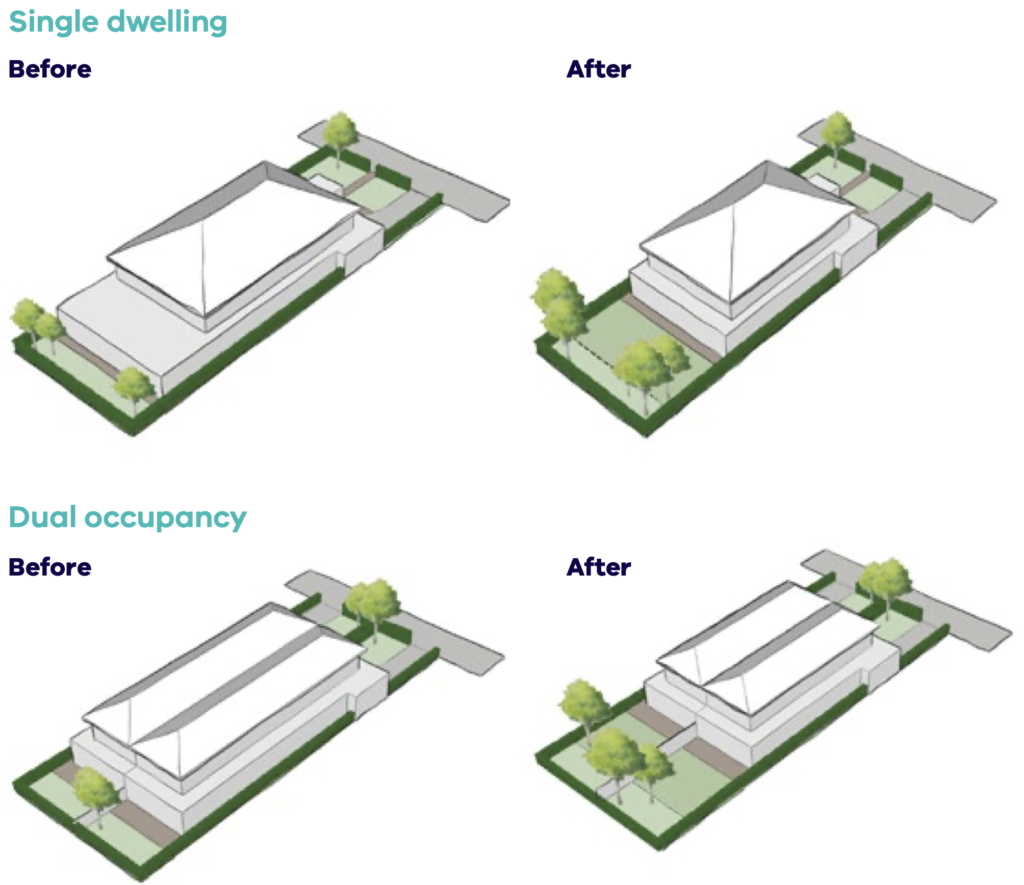

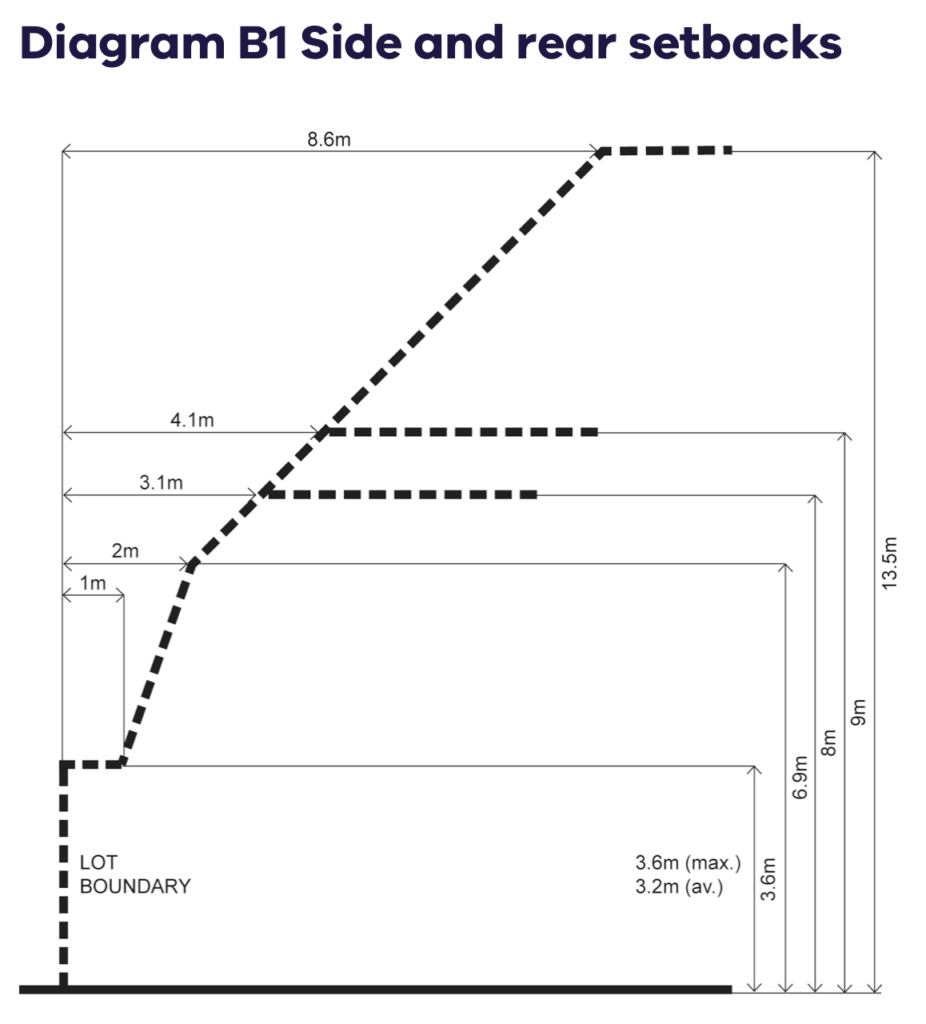

This is especially important for the side setback standard which, along with the wall on boundaries standard, establishes a tiered three-dimensional envelope. Even with all the confusion created by the deemed-to-comply standards debate, it has never been the norm for multi-dwelling development to “fill out” this envelope completely (the arguable exception is in the Residential Growth Zone, a scenario I return to below).4

A proper contextual approach to that envelope would, for example, look at where the adjoining open space is. It might push the buildings outside the envelope (closer to boundaries) where adjacent to existing boundary walls, outbuildings, or buildings without habitable room windows. (Most commonly, this might be the front half of a site, where buildings have traditionally been aligned). But a good contextual response will acknowledge the position of adjoining open space, or an especially crucial outlook, and may moderate outcomes in that part of the site in recognition of that circumstance.

Crucially, variations can occur in both directions. If an applicant believes a variation is warranted, they can argue for that variation as long as the objective is still met. And if a decision-maker or resident objector thinks a greater setback is warranted, they too can argue their point. In both cases, the Standard sets a baseline for that discussion, and it shifts the onus onto the person arguing for a variation to establish why that should be the case. All those judgements are then further contextualised by policy guidance.

The existence of this discretion has only become more important now that we have three commonly-applied residential zones (ResCode was designed at a time when almost all residential areas were in the one zone). The Neighbourhood Residential, General Residential, and Residential Growth Zones all should lead to different intensities of outcomes. Yet ResCode was never revised to apply tiered standards to the three zones. The discretion provided in ResCode has been important in allowing decision-makers to cover this gap.

Yes, discretion creates uncertainty. But this is a normal response to a complex situation. Black and white rules are always a notional ideal in regulatory design, but in practice it is highly challenging to frame them for complex application types without creating unacceptable outcomes. The designers of ResCode, as we have seen above, recognised this. They therefore accepted that discretion would be required to account for the nuances of character and context in particular situations.

It is, frankly, a little depressing to be having to outline at length that context and character are important in applying ResCode. But that is, unfortunately, where we are. Despite various disclaimers to the contrary, the fact is that the proposed changes would make both context and character largely irrelevant to a residential assessment.

So How Will ResCode Actually Change?

At this point it is worth outlining with more precision exactly how ResCode is proposed to be altered. The proposed changes are not a minor procedural tweak.

They dramatically shift the way that the quantitative standards are used, rendering them into deemed-to-comply standards. The controls have never been applied this way, and were not designed to be used this way, so the built form outcomes we can expect are unpredictable. It is clear, however, that outcomes would intensify.

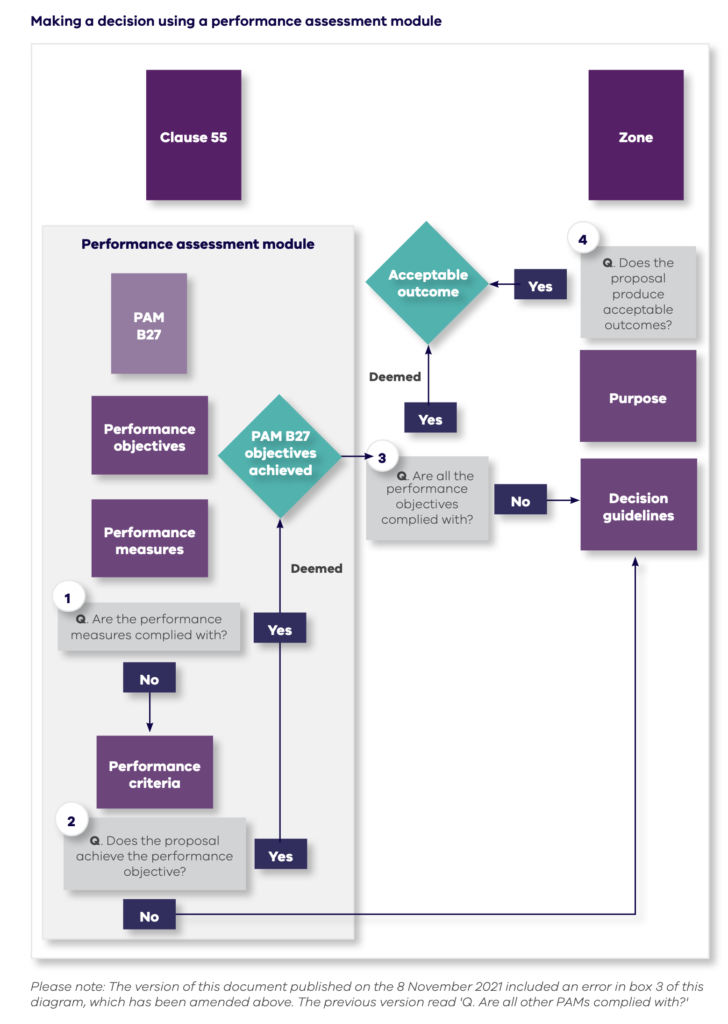

Under the proposed model, meeting the quantitative Performance Measures will be deemed an acceptable outcome of any given ResCode Objective. That means that any discussion of amenity would essentially end with the quantitative Standards / Performance Measures of ResCode – fit within those, and there is no judgement to be made. The ability to consider context (such as an especially sensitive piece of private open space) when making amenity considerations would be gone, as long as those Standards were met.

Additionally, six of those performance measures are then cross-referenced in the Neighbourhood Character objective. Those are:

- Street setback .

- Building height.

- Site coverage.

- Side and rear setbacks.

- Walls on boundaries.

- Front fences.

A proposal that meets those six standards is now automatically deemed to be acceptable from a neighbourhood character perspective.

One of several oddities about this is that three of the above standards are framed as amenity standards, not character standards (albeit amenity standards that are framed with reference to neighbourhood character).5 [Edited 9/12 – I somehow wrongly initially wrote here that all except fences were amenity standards, which is obviously wrong.]

Multiple Objectives that are traditionally considered vital to neighbourhood character outcomes that don’t have quantitative standards have simply been left out of the above list. So, for example, Integration with the Street, Landscaping, and Design Detail are out, creating an odd situation where those things can be considered as separate issue but cannot inform neighbourhood character discussions.

The model also largely strips away consideration of policy, with the operational provisions noting:

If the proposed use or class of development complies with any specified performance measures, it is deemed to achieve the relevant performance objective and the responsible authority must not consider and is exempt from considering… The Municipal Planning Strategy and Planning Policy Framework.

The same clause also strips out other clauses that allow the exercise of discretion (clause 65 and key parts of s 60 of the Act) in a manner similar to the way VicSmart clauses currently work.

By my reading, there is some marginal role for neighbourhood character policy here – for example, if a proposal is considered not to meet a Standard not on the above list, neighbourhood character could presumably be considered in consideration of that aspect. But it couldn’t be drawn on in the core neighbourhood character consideration.6 (I am staying with the default operation of the controls here – I will come back to the issue of customisation of the controls below).

Essentially, the model reduces residential character assessment to an envelope described by the combination of the quantitative ResCode Standards – if you fit within that envelope, your proposal is acceptable from character perspective. Because the Standards don’t vary by zone, that envelope will be relatively similar across all three main residential zones, despite the nominally different residential outcomes expected in those zones. (There will be some differences due to the requirements in zones that vary, such as overall height and garden area).

The first problem here is that changing standards designed to work as benchmarks or guidelines, as ResCode Standards were, into deemed-to-comply controls will intensify outcomes.

A deemed-to- comply control is a different kind of control to a benchmark control such as a ResCode Standard. Because it describes a situation that will essentially always be approved (either as-of-right, or in this case, needing a permit but more-or-less unrefusable) it needs to be set at a level that will only occasionally be unacceptable. In effect, a deemed-to-comply control needs to be more conservative than a benchmark control. Yet the ResCode setback envelopes, in particular, are much too permissive to be used in this manner.

Oddly, the paper makes no attempt to visualise the outcomes allowable under this model. Where are the diagrams that demonstrate the achievable envelopes in the zone to allow practitioners and the broader community to understand the outcomes now proposed? We saw a version of such diagrams when, for example, the Garden Area controls were introduced.

For a reform designed to introduce clarity and certainty about outcomes, the paper is conspicuously unclear about the forms we will see under its controls.

The absence of any visual modelling of deemed-to-comply outcomes is an important omission because the default achievable multi-dwelling outcome under this code will be significantly more intense than is the norm currently. Because the controls were not designed to work that way, and do not work that way currently, no analysis has ever been undertaken of the outcomes of using the ResCode envelopes in such a purely deemed-to-comply manner.

The change to using the controls this way is therefore lacking basic fundamental of its strategic justification. It also lacks sufficient clarity to properly inform public consultation on the changes.

We do have some hints from current practice in the Residential Growth Zone (RGZ), however. There, the expectation is that neighbourhood character and surrounding site context will change, so the weight given to such considerations is dramatically reduced. While policy can and does moderate outcomes in the RGZ, it is much more common to see medium density outcomes largely “fill out” a ResCode envelope.

On existing single dwelling sites (say in the 500m2 to 900m2 range) this has led to a recognisable pattern. Typically we see a row of two-or-three storey townhouses (the exact yield being dependent on lot size), often cantilevered over a driveway. The ground floor tends to be dominated by car parking and service areas, sometimes with a one-bedroom or a study nook. Because private open space requirements are less for decks than ground floor space, most of the dwellings rely on upstairs balconies as their open space. Yet in this configuration those terraces are facing side or rear boundaries for all but the front unit. This creates overlooking problems, which the Standard says can be addressed by fully screening the balconies.

These are not good outcomes. We have seen much wrangling at VCAT about how to go about infill in the RGZ, and councils have had some success in pushing back against the minimum compliance approach to ResCode in such circumstances. That process has, essentially, been an arduous case-by-case groping for the guidance on appropriate typologies that ResCode (in either its existing or proposed form) fails to provide. That has been a painful exercise, but in the absence of strategic work to prevent this needing the be thrashed out through the permit process, such applications have taken important steps in working through appropriate higher-yield forms. However the moderation that currently is provided by policy and contextual considerations would be almost entirely stripped away under the proposed model.

That side-facing townhouse form – without the moderation that sometimes occurs even in the RGZ due to the policy and context – would inevitably become the norm for infill in all residential areas, including the Neighbourhood Residential Zone. There would be some moderation in the NRZ and GRZ from the zone’s garden area and height requirements, but those requirements (because they were mandatory) were conservatively framed and in my experience will not dramatically limit the impacts to be caused by allowing the ResCode envelope to fill out.

(And, again, where the massing diagrams that would help us to consider all this? If I am wrong about the above, what do the framers of these reforms envisage the likely built form outcomes to be?)

The changes would bring residential controls full circle. This is how we used to do it – the 1960s and 1970s “six-pack” flats were the product of similarly mechanistic controls. Those buildings are not all bad, and have much to teach us about how we should go about achieving infill yield and more affordable market housing – a point I will return to below (I love the best six-packs, and think they should represent the starting point of how we reframe the residential controls). They remain, however, a largely reviled model in the wider community, mostly because the worst examples allowed by such codes were so bad.

To be fair, the ResCode reforms will I suspect, lead to slightly different forms. The classic six-pack flat building is a low-rise apartment, with shared car parking. The market these days seems to prefer townhouses with separate car parking (which in many ways ends up making the outcomes worse, as it can lead to more space lost to vehicle circulation). However what I expect will be shared with those older models is a similar lack of respect for context, especially in terms of massing.

Fully filling out the ResCode envelope will not be, as it is now, the edge-case outcome pursued only by particularly ambitious or shonky developers. It will be the endorsed outcome that the planning system says is appropriate.

When this occurs, developers should not be judged harshly. Fully filling out the ResCode envelope will not be, as it is now, the edge-case outcome pursued only by particularly ambitious or shonky developers. It will be the endorsed outcome that the planning system says is appropriate.

Importantly, that outcome will be known before the application is lodged. These applications will still, theoretically, be subject to a normal application process including notice and review. But having been deemed acceptable in terms of amenity and character before they are lodged, they will be essentially unrefusable. These applications will be a procedural farce, trying up council and VCAT resources when there is no meaningful assessment to be made.

If the state government and DELWP truly believe that these compliant designs will be acceptable outcomes then they should have the courage to own that outcome and make them as-of-right. Forcing local government to go through the motions of meaningless permit processes is a form of blame-shifting, making councils appear responsible for the outcomes they have no real ability to influence, and inviting residents to waste time and money (both their own, but also developers’ and councils’) on futile objections and appeals.

But What About Customisation?

All of the above talks about the default operation of the controls. One counter to my arguments above is that if the default ResCode situation is unacceptable in a given context, councils should do the strategic work to customise the Standards for their situation.

The realism of this expectation needs to be examined. We have always had similar mechanisms to customise ResCode, over and above policy – in the early days, this was the Neighbourhood Character Overlay, and in more recent times it has primarily been the schedules to the residential zones. Other tools, like the Design and Development Overlay, can also serve similar roles, especially in areas undergoing greater change.

The report notes on page 31, however, that there has been limited takeup of the NCO, stating:

Since its introduction in 2002 the NCO has only been applied in 15 planning schemes (out of 79) with 56 schedules. When considering residential land area, the application of the NCO affects an average of 3.10% of residential land in the 15 identified planning schemes and the impacts statewide are even less significant.

The report goes on to acknowledge that this makes the default operation of the controls very important. This is the first reason why I think it is fair to focus, first and foremost, on the implications of the default operation of the controls as discussed above.

What the report doesn’t reflect on, however, is the critical question of why the NCO hasn’t been taken up more widely. This is a crucial question, because the sidelining of policy means that the use of such customised controls will become much more important.

My own view is that the NCO wasn’t widely adopted for several main reasons:

- DELWP and its predecessors were resistant to its use, meaning that attempts to apply it were either unsuccessful, or councils simply gave up trying.

- DELWP more recently directed council to use customised zone schedules rather than the NCO – although even then there was also some resistance to such customisation.

- Policy guidance was found to do the job satisfactorily, and in some circumstances, better, so councils used it instead – especially given the resistance they faced to use of NCOs and zone schedules.7

If it is true that councils faced difficulty applying the NCO, or found policy preferable, then these are issues that should be dealt with before shifting to a model that relies heavily on a similar customisation process to avoid the problematic outcomes of the default controls.

Even if the Department is more forthcoming under the new paradigm about allowing such variations, councils face a considerable strategic challenge in undertaking that work, which the loosening of the default controls will make suddenly urgent. It is a pattern we have seen before and that I refer to in my book about the Victorian system as the “centralisation of problems and the delegation of solutions”. It is great to empower councils to better implement the policy objectives, but too often we have seen the state government allow problems to fester in the default controls and use the ability to customise solutions to fob the problems of fixing them off to local councils. Expecting councils to undertake the burden of customising their controls to fix the issues with this review is neither fair nor realistic.

There is also a real question about what modifications can be carried over from current policy to the new model. The deemed-to-comply model requires failure to meet a Performance Measure for any other considerations to apply; much existing policy could not be readily translated into such terms. This means a great deal of current qualitative guidance will be swept away without being readily replaced.

There may be many who would welcome such a scorched-earth approach to residential policy. For my part, I think there is a lot of merit in auditing existing policy, and as discussed below, reviewing existing conventions and guidance about how policy is written to allow it to be clearer. However until such work is done, those polices are legitimate parts of the scheme that have been through amendment processes. Councils, and the community, are justified in relying on such policy being applied and not lightly removed from their schemes.

We should be clear about the enormous implications of disallowing that existing legitimate policy and providing only limited means to reinstate it – especially given that this would occur alongside a simultaneous loosening of the default controls. I do not think the current paper appropriately acknowledges the enormity of what it proposes in this regard.

But Surely This Streamlining is Necessary – ResCode Applications Take So Long!

At this point, I suspect some readers will be saying something along the lines of: “okay, maybe, but the existing system is very complex, we need to do something – especially with regards to giving more certainty about outcomes.”

I have been undertaking ResCode assessments, and presenting cases about ResCode proposals at VCAT, for more than twenty years – the entire life of the control. I am not blind to the issues with ResCode. I talk about them for example, in my book (at pages 221-2), where I acknowledge that the success of ResCode in moderating the concerns about the outcomes of medium density housing has come at the price of reduced certainty of outcomes, and hence delays and disputes.

The statutory planners who work hard to assess controls under the current regime are not simply ticking boxes; their use of discretion is positively affecting outcomes, and is vital to achieving successful outcomes using these rules.

However, all those years of working with the controls – and with the residents, designers, and developers who grapple with them – has also taught me that the controls are doing meaningful work. The statutory planners who work hard to assess controls under the current regime are not simply ticking boxes; their use of discretion is positively affecting outcomes, and is vital to achieving successful outcomes using these rules.

That discretion cannot simply be removed from the system without redrawing the controls to cover the gap. To act as if the current ResCode Standards already describe an appropriate outcome and the whole system can be set to autopilot without further modification devalues all that work and misunderstands what is being done to achieve the outcomes that currently occur.

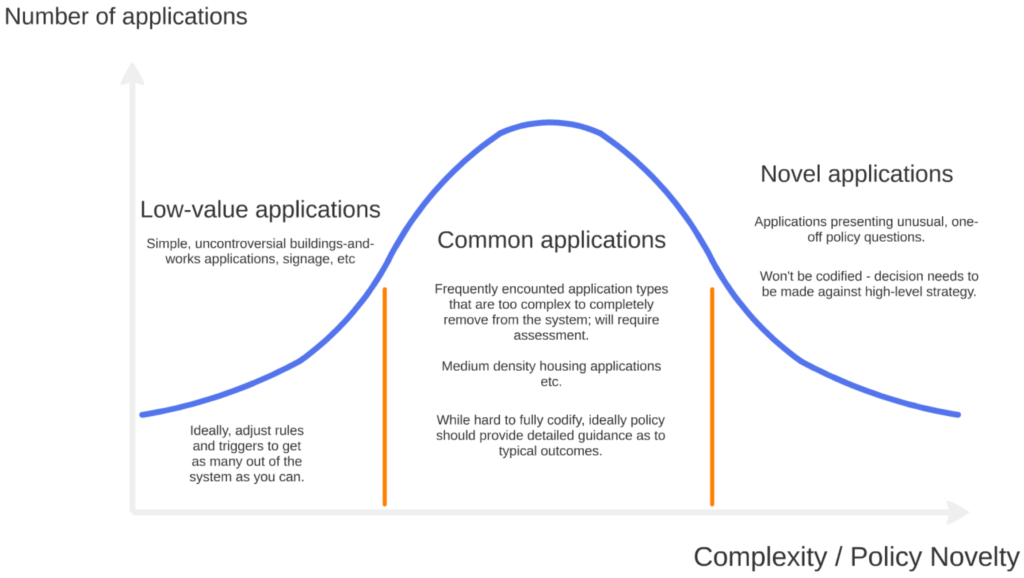

Furthermore, the proposed changes in my view do not recognise where planning discretion adds value. I have previously written that a well-designed planning system can be conceived of as a bell-curve related to the number of applications versus their complexity. On the left of this diagram, we have simple applications, which ideally we only see a few of (although that is always easier said than done in statutory design terms). On the right, we have novel and complex applications, which we don’t see often but which require a detailed assessment.

On that diagram, I used the medium-density applications that are now assessed against ResCode as the example of what sits in the middle of this diagram. These are applications that represent a familiar type of problem. We can and should anticipate these and create policy that can give clear guidance, but they will be too complex to codify. If the system is well-constructed, these are going to be the main day-to-day focus of the planning system.

I understand it is tempting to look at that fat centre part of the curve and see huge scope for benefits if we can reduce the number of applications in that bulge. This is true to a point. But the discussion needs to start from a recognition that the system is doing the work it is supposed to here. These applications are both consequential and numerous. Devoting time to getting them right, and having systems and codes in place that allow good assessment to be done, is a valid use of the planning system’s resources.

I don’t want to get sidetracked by a discussion about the broader system reform program (whether Smart Planning or the new post-Covid reform agenda recently announced), but my own view is that Victoria’s problem is not what is happening in that fat curve. It is that the line on the left third of that diagram is far too high, because our system is poorly targeted and creates too many meaningless assessments. There is a whole story in itself about how our reform program has mishandled its approach to the of third of that diagram that I won’t recount here.

I mention it, though, because all parts of the system are connected. The delays in handling residential applications are not purely the products of the residential controls. Medium density housing applications are held up because of the accumulation of other demands on council planners resources created by various other longstanding system problems: poorly targeted buildings and works triggers in industrial and commercial zones; overlays defaulting to requiring permits for all buildings and works; resource being diverted to meet unfeasibly short timeframes for VicSmart applications; having to interpret and apply covenants as part of their assessment; antiquated parking controls; and so on. The last decade of reform has, perversely, only made the system more complex to administer, for reasons I have discussed elsewhere.

Again, this is not to get distracted from the current issue by pointing to the array of other systems problems. There absolutely are opportunities to improve ResCode which should be pursued without delay, and these are discussed below. My point in raising these issues is to make the point that I don’t think many of those planners handling medium density applications think that this work is a poor use of their time; and I don’t think the community wants that assessment process drastically stripped back. And while developers of course want quicker assessments, I do not think most see ResCode processes as an example of the system being fundamentally misdirected. I also suspect most would acknowledge that the really consequential delays are caused by third party rights and appeals – and even if that were warranted, there is little political appetite for any overt rollback of those rights.8

We should be reviewing ResCode, for a number of reasons, including but not limited to improving the speed of assessment and clarity of outcomes. But we need to recognise that system outcomes need to be addressed holistically; that system streamlining of any given planning tool needs to recognise the complexities of the assessment being undertaken and ensure that the assessment is still doing its job; and that strategic work and community consultation will be required to design appropriate tools to achieve the outcomes that justify the involvement of planners in the first place.

Yes, we should be looking at a review of ResCode that improves both its efficiency and its efficacy. But we need to do the actual work to design those tools properly.

So What Are the Actual Problems with Our Residential Assessment Framework?

As I have said, ResCode does have a number of problems that need to be fixed. Because the current paper mis-states those problems, it pursues misguided solutions. However there are number of genuine problems, which affect both outcomes and speed.

We Have Chased An Unuttainable Goal of Certainty (When We Should Be Seeking Clarity)

My point above is that the delays caused by ResCode need to be contextualised by an understanding that these are complex assessments. That doesn’t mean I don’t think that delays are sometimes unreasonable, or that there is no scope to improve the timeliness of ResCode assessments.

What is important, however, is to understand what factors can tip those delays from being proportionate to the complexity of the assessment into being unreasonable. This is the question I don’t think the current paper has a strong handle on. In my view these excess delays are caused by a combination of factors including:

- Lack of clarity in terms of expected outcomes under the current framework.

- Confusion about operation caused by the unfixed Operation clause.

- The range of other workload factors created by the system outside of the residential framework.

The discussion that follows expands on some of these points, in particular the reasons for lack of clarity.

With regards to the issue of clarity, I also think it is important that this is distinguished from the issue of certainty. The two have often been treated as interchangeable in system reform discussion, and the pursuit of certainty has led to the introduction of mandatory height and garden area controls. But I do not think absolute certainty can realistically be provided for complex applications, because it requires hard-coded settings (making things as-of-right or prohibited) that are only suited for the clearly-acceptable or the clearly-unacceptable.

Most medium density housing applications live somewhere in the middle, and in such cases absolute certainty is an unreasonable goal. What we really need to provide, as much as possible, is clarity for those applications. And once we are looking to provide clarity, we turn away from prohibitions and deemed-to-comply solutions, and towards benchmark standards and more descriptive policy.

The Operation of Standards Has Been Distorted by Drafting Errors in the Operation Clause, Leading to Confusion and Conflict

I have covered this at length already. The consistent failure to correct the Operation provisions in ResCode clauses leads to conflict and delays. If the state government wishes to pursue a model that changes how Standards work, it can do the work to allow that to occur (and I have suggested ways that a partially deemed-to-comply approach could be incorporated below). But in the meantime, leaving an Operation clause in place alongside controls that were not designed to be used that way is contributing to conflicting expectations and hence delays.

There is Confusion Between Maximums, Benchmarks, and Deemed-to-Comply Controls

This is obviously at the core of the Standards problem described above, but it also seriously affects the operation of the height and garden area controls that are provided in the zones. These are expressed as maximums which can never be varied.

This was obviously to provide certainty. This epitomises the confusion between providing certainty and clarity. A maximum that should never be varied presumably represents the edge-case of what is acceptable. It provides certainty in the sense that applications cannot be approved beyond that threshold. But in the absence of any further guidance, they do not provide sufficient clarity about what should be the typical outcome.

Is it anything up to the maximum? If so, that creates an odd situation where a one-centimetre difference would tip something from presumed acceptable to completely out of the question. And the height and garden area controls are – quite properly given they are mandatory – set at permissive levels. Because the controls do not sufficiently explain what are typical outcomes, applicants point to compliance with the maximums as justification for the acceptability of a proposal. This leads to poor outcomes.

Site Coverage, Open Space, Garden Area, Permeability and Landscaping

The addition of garden area controls into the mix, well after the other controls, has led to a jumble of controls that address the balance of built form and landscaping across a site. There is logic to this, as these are conceptually distinct considerations, but I think most users of the system would agree that there should be some rationalisation of these standards and controls to simplify their operation.

The Controls are Ill-Suited to High Change Areas, and 3- and 4-storey Buildings

ResCode, at its heart, is a tool designed for moderate change outcomes where the predominate infill is villa units and two-storey townhouses that represent a marginal change on their existing context. Its emphasis on assessment starting with existing conditions (rather than a desired end state) means it struggles to productively guide change in areas where substantial or even wholesale change is sought.

Furthermore, because the design approaches it encourages implicitly assume townhouse or villa unit forms, it doesn’t work well for assessment of the 3- and 4-storey forms that are increasingly important to meeting our housing needs. (I perhaps have sounded opposed to 3 and 4-storey buildings in these comments. I am not. I am, however opposed to the forms that typically result if buildings of such heights designed using the ResCode Standards – especially if the qualitative elements are stripped away.)

Buildings of such height need different approaches to work well, notably the consolidation of bulk in less sensitive parts of the site (usually the front) and the consolidation of open areas into large portions (especially at the rear) to provide more effective breaks between buildings and decent canopy planting. Consolidated car parking is also highly desirable, as opposed to the private garages encouraged by ResCode.

There Are No Tiers in the Standards for the Different Zones

As already touched upon, the absence of any tiered Standards means that the default situation in ResCode is mostly the same for the three main residential zones. This is a major hole in the current design (and one which is made much worse if qualitative considerations are stripped away).

It is true that Councils can customise the Standards for particular areas. But it is important that the standard controls set a default situation, both to send a signal about where that customisation discussion should start, and to avoid unnecessary strategic work where the default level is appropriate.

Policies Have Been Devalued

Local policy provides, in my view, a crucial mechanism to cover many of these problems. Yet as I have already argued, there has been a steady process of devaluing local policies going back to the 2007 Making Local Policy Stronger review, and exacerbated by the PPF restructure (which forced separation of neighbourhood character and housing supply policy into separate clauses, making it harder for one policy to clearly outline the desired balance of these considerations). Councils have been pushed towards endless zone schedule customisations to guide their outcomes, which can be a useful tool but should not be seen as the only legitimate approach.

Policies are Not Descriptive Enough

The process of reclaiming local policy needs to involve a push towards more descriptive, typology-based policy. The job of policy should be to describe the typical outcome with as much as clarity as possible, so that decision-makers can then judge whether context in a particular situation warrants a more- or less-intensive response than the typical outcome. However under prevailing norms of how policy is written in Victoria, councils have rarely been able to be as clear and descriptive as would be desirable.

Overlooking and Open Space Standards Encourage Poor Outcomes

I’m getting into the weeds here, but I’ll throw in one particularly specific issue as it will become especially prevalent if these reforms are adopted. ResCode requires less open space for balconies than it does for ground level. This incentivises the use of balconies, which in the centre of the site creates overlooking concerns. ResCode then allows resolution of that issue by fully screening those balconies. This is a poor design approach that flows inevitably form the minimum compliance approach to the tools. It is currently only the qualitative elements of ResCode that prevent this approach becoming far more widely adopted.

And so on…

The issue above is already getting more detailed than I wanted to get here. Suffice to say that there are a range of Standards that could be improved to get better outcomes. ResCode hasn’t been comprehensively reviewed since it was introduced; its Standards require revision – especially if there is any contemplation of making them deemed-to-comply.

How Should These Issues Be Fixed?

In many cases, the discussion above should make the required responses reasonably clear. However I will spell out where I think we should start.

Fix the Operation Clause and Practice Note to Reflect How ResCode Was Designed

The lack of clarity about the Operation clause contributes to conflict, and hence delay, and needs to be fixed. It therefore needs to be clarified to work as originally intended. The ResCode Practice Notes need to have their original wording about this point reinstated, and the various documents that have since started to endorse deemed-to-comply Standards (such as the Practitioner’s Guide) brought into line with the intended operation.

It is inappropriate to wait for the outcomes of this review to fix this issue. We know how the control was supposed to work, and the remedy is simple.

Those who want to change the operation of Standards need to make their case and, crucially, come up with Standards designed for deemed-to-comply usage. The current proposals will take some time to work through, especially if, as I suspect (and hope) the state government hesitates when it realises how radical the proposals are. We should stop muddying the waters by rolling in a discussion with possible reforms with the issue of how the control is supposed to work now.

It’s a drafting error. The fix should not be further delayed.

Clarify Guidance About As-of-Right, Deemed-to-Comply, Benchmark, and Maximum Standards

There is too much slippage between different types of development standards currently. We need to improve standard formulation of controls so that the system always properly distinguishes between (and makes smart judgements about when to apply) the following different types of development standard:

- As-of-right controls: controls where compliance means a permit is not required.

- Deemed-to-comply controls: where compliance means a particular Objective is deemed satisfied.9 Such controls usually allow discretion to be exercised in the developer’s favour, but preclude it being exercised in favour of neighbours.

- Benchmark controls: where controls provide guidance about a typical outcome, but circumstances may warrant either a more or less permissive outcome. Such controls allow discretion to be exercised in favour of either objector or developer.

- Maximum controls: These indicate the maximum outcome. Where made mandatory, these should frame the describe the most intense acceptable outcome, and not necessarily (unless some contrary intention is expressed) be understood as a typically acceptable outcome.

Proper clarity about this would remove the need for the complex new Performance Assessment Module framework proposed in the paper. I have previously written about the trend in previous reforms to gradually make the scheme more complex by the addition of repeated new procedural and worklfow tweaks, when the VPP design already allows plenty of scope to make the system flexible using customised system settings.

We don’t need to keep adding new workflows. Just clarify the operation of controls in the workflows we have!

Tiered ResCode Standards for Different Zones

This flows inevitably from the comments made above. Tiered standards are vital to the effective rollout of the new zones. They are even more essential if the controls become deemed-to-comply, because that will largely collapse the distinction between residential zones and make outcomes far more intense than has been the norm in the lower-tiered residential zones. However, even without that change, tiered standards would provide invaluable clarity and prevent councils starting from scratch in both strategic work and permit assessments.

Re-Embrace and Clarify Policy

Again, this flows from the points already made. There is a depressing sense that policy is increasingly seen as borderline illegitimate, a backdoor mechanism councils use to undermine state policy and which confuses the clarity supposedly provided by the standard controls. But it only does so if poorly justified or written.

The solution to poorly-written policy is not removal of policy; it is better-written policy. Good policy provides guidance and therefore clarity, and the Practitioners Guide and other documents should be reprioritising policy as a central mechanism that can be used to help increase everyone’s understanding of what residential outcomes are sought.

That embrace of policy should be built around a new paradigm about how residential policy is written, encouraging the use of diagrams to indicate the indicative forms and massing that are desired in typical situations. Such an approach helps to provide the clarity about the preferred end state that the current system fails to provide, especially in areas targeted for significant change.

The re-embrace of policy does not mean there is not a role for customised zone schedules and other such tools. However we need to avoid a dogmatic approach where useful tools at our disposal get sidelined because of arbitrary rules (sometimes unwritten) about which regulatory tools are preferred.

A 3- to 4-Storey Building Code

We have clause 57 sitting there vacant. It needs to be used to provide better tools for the design and assessment of 3- and 4-storey buildings. To work well, these buildings require more discernment in where massing occurs than ResCode (especially in deemed-to-comply mode) encourages. The typologies and design approaches for successful buildings this scale are completely different to those encouraged by ResCode.

This is, to be clear, a big job. It would require significant road-testing of new Standards. But this is all the more reason work needs to start now.

Design Purpose-Built Deemed-to-Comply and As-of-Right and Standards

If there is still a desire for more clarity, there is potentially a role for either as-of-right or deemed to comply standards. I am not opposed in principle to such controls. However, the Standards need to be set with regard to the type of control proposed. This means that they need to be consdierably more conservative than the current benchmark Standards under ResCode.

Where properly designed, we can also consider controls that are actually more facilitative than proposed. It is far better to design controls to get applications out of the system completely. The current proposal’s adoption of deemed-to-comply Standards that still need a permit creates a sort of zombie permit process, still taking up space in the system but largely unable to be influenced by human judgement. I am not sure what the value-add of the planning system is in such a scenario.

In my view, the better balance is a system that makes clearly acceptable development as-of-right. This could facilitate models such as single storey units in the rear of properties that were well off boundaries, while retaining the permit process discretion for more conventional medium density applications.

Empower Councils to Facilitate Favoured Development Models

As an augment to the above, we should give councils more ability to get applications off their desk by creating their own permit exemptions. Currently councils can roll-their-own VicSmart categories, but this is just placing more applications on the ceaselessly moving conveyor belt for statutory planners to slog through.10 We need to allow councils to tailor controls that get applications out of the system, providing genuine relief for the planning departments, and facilitating favoured forms of development.

That can also be done at a state level, but councils could apply even more carefully customised controls at street-by-street level. More than seven years ago I suggested a Facilitated Form Overlay to allow this to occur; I still think it’s a good idea.

In addition to empowering councils to solve their own problems and encourage good local outcomes, such a tool would also become a valuable proving ground for codes and approaches that could then be implemented more widely. Too often, it has felt as if state government sees local councils as troublemakers needing to be kept in check. Tools such as the FFO would help engender a culture of empowering councils to be innovators who could pioneer approaches that can then be applied elsewhere.

Conclusion: A Missed Opportunity

The current proposal essentially takes a shortcut. The solution it proposes would cause such a radical change to outcomes that I suspect that the paper’s authors don’t quite realise the implications of what they propose. It is the equivalent of looking at a somewhat beaten-up and underpowered car and fixing it by cutting the brake lines.

I suspect once it is widely appreciated how drastic a change it contemplates, the approach will be abandoned or significantly watered down. Yet there is, as I have outlined above, much that should be done to improve the operation of ResCode. Unfortunately, those solutions – some of which are simple, but some of which would require significant consultation and further work – do not seem to be on the radar.

This is frustrating. An opportunity has been missed to canvas options that would improve clarity of outcomes without sacrificing context and character outcomes.

1 Most lawyers, in my experience, lean to that view based on the simple reading of the clause, and certainly these words in isolation seem to support that interpretation (though I wish I’d seen more legal opinions on this that actually incorporated a discussion of intent). However a couple of factors (beyond intent) mean that this is not in my view clearly the case. First, the wording is in my view not quite definitive, given the odd phrasing “requirement to meet” – if the intent really was for the controls to be deemed-to-comply, then this could have said “a standard specifies an outcome that is deemed to meet the objective” or similar. Second, as the Tribunal has noted in decisions rejecting the deemed-to-comply reading, this approach cannot be reconciled with the remainder of the Operation clause, notably that the responsible authority “must consider” the Decision Guidelines when considering if the Objective is met. They cannot do so if the Standard is deemed-to-comply, since this would render the Decision Guidelines moot.

2 The paragraphs that follow draw from my work on those editorials.

3 The paper quotes the conclusion of both pro-deemed-to-comply decisions it mentions, but does not explicitly reference the conclusions of either case that rejects the approach. It also, in my view, misrepresents the second such case it quotes (Lamaro v Hume CC & Anor [2013] VCAT 957), by saying it “attempted to rectify the mandatory requirement to consider the decision guidelines when assessing a standard.” The verb “rectify” is odd here, as it presumes the intended operation of the control is a problem that needs to be fixed. I see no basis in Lamaro for thinking the Tribunal in that instance saw such a problem – rather, the Tribunal fully (and in my view, correctly) accepted that ResCode, by design, had both quantitative and qualitative considerations to be applied in considering all the objectives.

4 This is as good a point as any to acknowledge that it is true that single dwellings that are subject to only the building system use ResCode in a more-or-less deemed to comply way. However the risks here are lower, because there are not the same incentives to completely maximise envelope for a single home as there are for unit developments, and the overwhelming majority of residents simply won’t build a house big enough to fill out the envelope. (In the occasional cases where people do, as can be seen sometimes in extremely affluent neighbourhoods, the outcomes are indeed pretty awful.)

5 This is important because it highlights that character and amenity cannot be neatly siloed as separate issues, since built form character of an area will properly inform resident’s reasonable expectations with regards to amenity. As so often in planning, good decision-makers need to be able separate issues into distinct considerations, while not losing site of the links between them. These subtleties make it hard to properly frame controls in simple deemed-to-comply terms.

6 It should be noted, though, that there are all puzzling inconsistencies in the way the proposed clauses are drafted. For example, there remains a residential policy objective, which seems to me activates policy considerations (which surely includes neighbourhood character policy) in a way hard to reconcile with the framing of the Neighbourhood Character clause. A unit proposal might be deemed, by virtue of its envelope, to meet the Neighbourhood Characater clause but could theoretically at least then fail the Residential Policy clause on character grounds. This is an extension of the inconsistent approaches already seen when existing standards are used in a deemed-to-comply manner.

7 While I suspect this comment will annoy some who place a premium on certainty and / or clarity above all else in regulatory design, in my view there are circumstances where it is impractical to map the exact areas where a statement of general principle should apply – in such circumstances, policy (which can then be informed by the judgement of decision-makers) works well, because it avoids creating the artificial impression of precision that comes with the sharply defined edge of an overlay boundary.

8 Of course, gutting the controls so that such appeals cannot be successful is a form of rollback by stealth. I don’t foresee a government actually admitting its intent is to remove third party appeal rights in the near future, however.

9 This term is often used to refer to what I have called as-of-right controls as well; given the discussion around ResCode has been about Standard compliance being deemed to have met Objectives, but not being made as-of-right, I have continued to use “deemed-to-comply” in this sense for consistency.

10 A note to any local government strategic planners reading this: please don’t create local VicSmart categories. You are creating garbage, morale-sapping, staff-burning busywork for your statutory planning colleagues.